|

|

|

|

|

The Wartime Memories Project is the original WW1 and WW2 commemoration website.

Announcements

- The Wartime Memories Project has been running for 24 years. If you would like to support us, a donation, no matter how small, would be much appreciated, annually we need to raise enough funds to pay for our web hosting and admin or this site will vanish from the web.

- 10th April 2024 - Please note we currently have a huge backlog of submitted material, our volunteers are working through this as quickly as possible and all names, stories and photos will be added to the site. If you have already submitted a story to the site and your UID reference number is higher than 263893 your information is still in the queue, please do not resubmit, we are working through them as quickly as possible.

- Looking for help with Family History Research?

Please read our Family History FAQ's

- The free to access section of The Wartime Memories Project website is run by volunteers and funded by donations from our visitors. If the information here has been helpful or you have enjoyed reaching the stories please conside making a donation, no matter how small, would be much appreciated, annually we need to raise enough funds to pay for our web hosting or this site will vanish from the web.

If you enjoy this site

please consider making a donation.

Want to find out more about your relative's service? Want to know what life was like during the War? Our

Library contains an ever growing number diary entries, personal letters and other documents, most transcribed into plain text. |

|

We are now on Facebook. Like this page to receive our updates.

If you have a general question please post it on our Facebook page.

Wanted: Digital copies of Group photographs, Scrapbooks, Autograph books, photo albums, newspaper clippings, letters, postcards and ephemera relating to WW2. We would like to obtain digital copies of any documents or photographs relating to WW2 you may have at home. If you have any unwanted

photographs, documents or items from the First or Second World War, please do not destroy them.

The Wartime Memories Project will give them a good home and ensure that they are used for educational purposes. Please get in touch for the postal address, do not sent them to our PO Box as packages are not accepted.

World War 1 One ww1 wwII second 1939 1945 battalion

Did you know? We also have a section on The Great War. and a

Timecapsule to preserve stories from other conflicts for future generations.

|

|

Want to know more about Stalag Luft 1 Prisoner of War Camp? There are:72 items tagged Stalag Luft 1 Prisoner of War Camp available in our Library There are:72 items tagged Stalag Luft 1 Prisoner of War Camp available in our Library

These include information on officers, regimental histories, letters, diary entries, personal accounts and information about actions during the Second World War. |

|

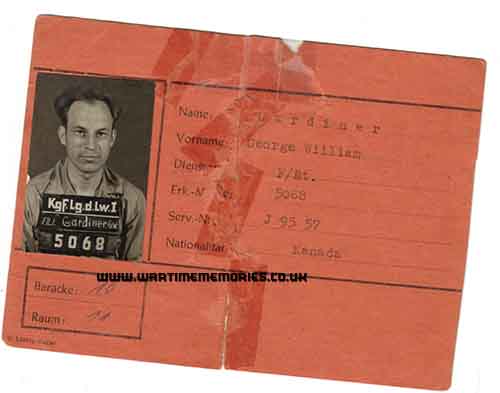

F/Lt. George W. Gardiner 429 Squadron My dad, George Gardiner was on his 23 mission on July 18th 1944 when his plane was hit from falling bombs from above Aircraft Halifax LW127. Went down 3 killed 3 POW's and 1 made it back to friendly lines. Phil Brunet was in the same camp and bunk house.

|

Sgt. Clifford Webb MBE. 21 Squadron We believe that my father Clifford Webb was captured twice.

This article was found which was probably written by our father to his mother after the second capture/escape. If anybody can shed some light on Clifford Webb, it would certainly be most appreciated !

The article Letter home from Sgt. C. Webb, RAF, from “Woodside”, Homer, aged 24 years. C. 1940.

We were shot down in France, near Calais, on June 14th, by six Messerschmitts, but nobody was injured, so we tried to make our way back to England. We found a little boat three days after the crash, but had no chance to stock it with food and drink.

Our oars were very weak and soon broke. The upshot of it all was that we were in the channel for three days without food or drink and not a stitch of dry clothing on us. One of my companions died on the last night and the two of us left were washed back on the French coast, still behind the German lines.

We hid for two days to regain our strength, and started walking to Le Havre about 50 miles away, but abandoned the idea as the port was too closely watched. Then we tried to get work on the farms, posing as Belgians, but failed because we had no identification papers. We begged bought and stole food and civilian clothing during this time.

Eventually we decided to go north and try to cross the Channel again, but were unlucky enough to walk into a hidden German aerodrome, just south of the Somme. We were stopped and questioned; I was the only one speaking French. They found out my companion was English so I was taken as well. This was on the evening of July 1st.

I don’t know how I escaped, but all the people in this camp are the same. Some of the escapees from crashes are nothing short of miraculous.

Report of incident near Calais.

14/06/1940: Merville, France.

- Type: Bristol Type 142L, Blenheim Mk. IV

- Serial number: R3742,YH-?

- Operation: Merville

- Lost: 14/06/1940

- Pilot Officer William A. Saunders, RAF 40756, 21 Sqn., age 20, 14/06/1940, missing

- Sgt W.H.Eden PoW also initialled H.W.Eden

- Sgt C.Webb PoW

- Airborne from Bodney. Crash-site not established. Last seen being chased by Me109s.

- P/O Saunders has no known grave and is commemorated on the Runnymede Mmemorial.

- Sgt W.H.Eden on his 30th operation evaded until captured July 40 near Doullens after spending 3 days in a rowing boat and interned in Camps L1/L6/357, PoW No.87.

- Sgt C.Webb was also captured with his comrade but was interned in Camps L1/L3/L6/357, PoW No.76.

|

Fred W. Butler I was a POW at Stalag Luft 1 Barth from Feb 1944 to May 1945 and was one of twelve "Kriegies" who decided to walk to freedom and out of Germany from North Compound I. I was accompanied by Harry Korger, Bill Reichle and Bill Dallas to name a few. The rest of the names escape me. It was after the Russians had arrived and they helped us by ferrying us to the mainland by boat two at a time. I'm trying to remember the whole story.

|

W/O L. W. C. Lewis 514 Sqd. W/O Lewis survived the loss of Lancaster DS822 JI-T when it came down at La Celle Le Bordes France on the 8th of June 1944 whilst on a bombing raid to Massy Palaiseau. He evaded capture until the 16th of August and was then taken to Stalag 12a and later to Stalag Luft 1.

|

Wing Cdr. William David Gordon-Watkins DSO DFC DFM 15 Sqd Wing Cmdr Gordon-Watkins was the Commanding Officer of 15 Sqd. He was shot down on the 16th of November 1944 whilst piloting the lead bomber on a mission to Heinsburg. He was the only member of the crew to survive the incident and was captured and held as a prisoner of war in Stalag Luft 1. He had completed over 50 operations and had previously served with 149 sqd.

|

Sgt. Douglas Wilmott Waters No. 214 Squadron Douglas Waters flew with No. 214 Squadron, he was held as a Prisoner of War in Stalag Luft 1.

|

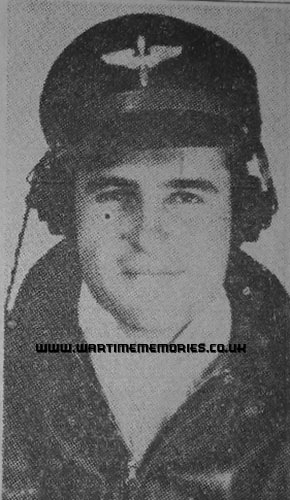

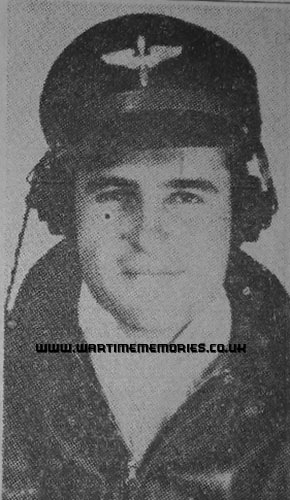

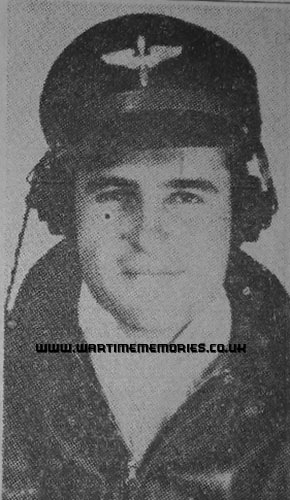

F/O. James Nicholas Hentges 338th Bombardment Sqdn. 96th Bombardment Group      My grandfather Jim was a 2nd Lt./Flight Officer and bombardier in WWII. He was born on 9 December 1923 in LeMars, Iowa, and had two brothers and one sister. At some point during his childhood, his family to Orange County, California, where he graduated from Santa Ana High School.

He enlisted with the US Army Air Corps on 11 December 1942, just two days after his 18th birthday, in Santa Ana, California. He did his preliminary training at the Santa Ana Army Air Base. His brother, William Hentges, Jr. joined the Navy and was a Seaman, 1st Class, assigned to an Amphibious Branch and stationed somewhere in the South Pacific. I am told that my grandfather completed his bombardier training at Deming Army Air Field, in Deming, New Mexico and graduated with the Class of 44-08.

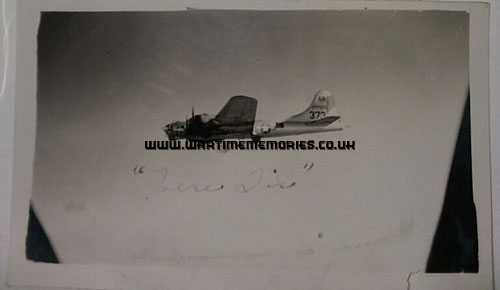

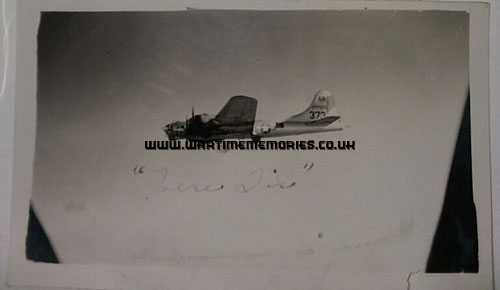

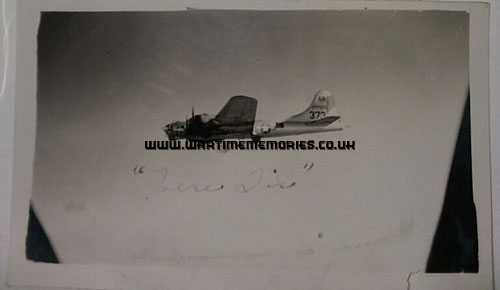

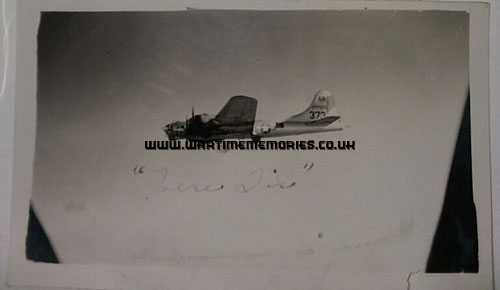

I was given two photos of my grandfather by my father and was told that the plane in the photos was a training aircraft assigned to the Ardmore Army Air Field, in Ardmore, Oklahoma, which was a four engine aircraft training base. Here is information I received about the aircraft that is reportedly the one in the photos my dad gave me (I don’t know if my grandfather was at any of the following locations during his training):

- Aircraft delivered to Cheyenne AAF, Wyoming on 23/02/1944

- To Great Falls AAB in Montana on 26/02/1944

- Back to Cheyenne on 02/03/1944

- To 222 BU Ardmore on 30/08/1944

- To 332 BU Ardmore on 19/06/1945

- To 370 BU Sheppard AFB in Texas on 19/06/1945

- Back to 332 BU in Ardmore on 26/02/1945

- Sold to the Reconstruction Finance Corp. on 24/08/1945 and scrapped at Walnut Ridge AFB, Arkansas

My grandfather told my dad that they flew their planes to England, stopping in Greenland to re-fuel. He said that was the quickest route to get there. On 2 October 1944, he was assigned to the 338th Bombardment Squadron, 96th Bombardment Group (Heavy), 3rd Bombardment Division, 45th Combat Bomb Wing, 8th Air Force and stationed at Snetterton Heath Air Field (AAF Stn: 138-ETG, RCL: BX-A), known as the ‘Snetterton Falcons’ and home to everyone’s favorite mascot, Lady Moe the donkey.

I have been unable to locate information on his first 6 missions. But I do have some information on his 7th mission, which was his last. He was the bombardier on B-17G-90-BO, a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress (airplane #43-38644, nicknamed “Green Weenie”).

The winter of 1944-45 was the coldest on record in 54 years. Their target on 5 December 1944 was an ordnance plant located in Berlin, Germany. The weather was not good. With low clouds making visibility nearly impossible, and strong, changing wind gusts, it would be dangerous and difficult. Dangerous because they needed to fly lower and get under the clouds to get a good visual of their target, and, with the changing wind and weather, difficult to calculate the precise time to drop the bomb load on the specified target.

Don’t forget the hours-long flight, the tiny, cramped spaces, and crews battling exhaustion and fatigue and having to wear electric suits that at times would malfunction and catch fire. Heated gloves, if removed to help a crewman in trouble or to pull a ripcord, could mean the loss of fingers due to frostbite. And hard, heavy metal helmets that moved all around and were a struggle to keep on, and that were supposed to help your protect your head in case a bomb hits and blasts apart the aircraft, but in reality were more like a big bullet because when the blast hit, the helmet flew off your head and shot through the aircraft, leaving nothing in its wake.

Don’t forget the very important, big, bulky oxygen masks. The warplanes were not like the modern ones of today. They weren’t equipped with pressurized cabins. Those masks were a lifeline, and one little leak or a few too many minutes trying to outrun the enemy’s fire could cause you not to have enough oxygen left to complete your mission and get back to base. Dizziness, confusion, panic, and paranoia would then set in - almost always a death sentence for all aboard.

No wonder the loss of life was so great. The odds kept stacking against them. With each new mission, the odds of being able to complete the mission and make it back to base uninjured and alive became slimmer.

Based on eyewitness accounts and crew statements, my grandfather’s flight was at about 28,000 feet over their target when they started taking on lots of flak. I assume that most or all of their bomb-load was had already been dropped because somehow they were hit by flak that came in through the open bomb-bay doors and started a fire. I read that if planes were hit with full loads they would explode upon being struck, with no chance of survival. My grandfather told my dad that flak shrapnel went straight through the plane. It caused a small fire, but they quickly put it out.

But by then they were also taking on enemy fire from three German ME-109s. That’s when they got hit. They lost one engine, then two. My grandfather said they were down to one engine when they bailed out. One eyewitness stated that my grandfather’s aircraft was able to shoot down one of the ME-109s before he lost sight of the plane and its crew. Eyewitness and crew reports agree that when first hit, the aircraft appeared to be out of control. But then the pilot, David Monroe, managed somehow to regain control of the aircraft and took it straight up into the thick, dark clouds. The same clouds that once caused them danger and difficulty now provided them safety and protection from the remaining two ME-109s.

All ten crew members of my grandfather’s B-17 were able to bail out and land safely, with no one suffering from any major injuries. When asked months later, one crewman stated that the Green Weenie’s crash site was about 30 miles from Berlin, Germany. They were quickly captured by German soldiers southeast of Parchim, Germany, and taken to a POW camp called Stalag Luft 1- North 3, in Barth, Germany. Four days later, on 9 December 1944, my grandfather spent his 21st birthday (most likely in solitary confinement) awaiting interrogation by the Germans, as was customary for new prisoners. I have read that they could be in the interrogation rooms for a week to a month, or for some even longer. The Germans would try just about anything to get the men to talk.

I recently read about the conditions of Stalag Luft 1, where my grandfather and his crew were held. There were only two latrines for 2,500 men. Toward the end of the war, they received only one bowl of soup (that was mostly water) and a piece of bread per day. Bunks, if they can be called that, were so low that you couldn’t sit up on them and were stacked four high. They were each furnished with a straw-stuffed bedroll. Maybe there was a thin blanket, but never a pillow. I read that POWs called them mortuary slabs, because that’s about what they looked like.

My grandfather was one of the lucky ones since he was assigned to the officers’ section, the ‘better’ section. I can’t even begin to think what the other sections must have been like. The American commander of their barracks in the North 3 section was WWII fighter ace, Francis ‘Gabby’ Gabrowski. My grandfather told my dad he was in the same barracks with Gabby and that he was loud and arrogant as all hell!

They were finally liberated by the Russians and released on 30 April 1945. He and his crew touched US soil on 2 June 1945. Most of them, like my grandfather, had jobs to do, families to raise, and just didn’t speak much of their time in the war.

My grandpa married my grandmother, Helen Louise (Mitchell-St. Clair) Hentges in 1956. From a previous marriage, she had a son, my father (Michael St. Clair, born July 4, 1947), whom my grandfather raised as his own son. My dad never really knew his real dad, (Walter James St. Clair, also a WWII US Army Air Force veteran), because he and my grandma divorced soon after my dad was born. By the time I tracked him down, he had already passed away.

My dad is an Air Force veteran as well, and served in Vietnam. I was born at Eglin AFB in Okaloosa County, Florida. Three weeks after my birth, my mom brought us to California, where my dad joined us after being discharged from the service.

My grandpa Hentges was a wonderful grandfather! He took us fishing, horseback riding, took us to the pizza parlor and gave us pennies to ride the mechanical horse! He even met us drive his work van (well, we got to steer the van while he worked the pedals, but to us we were driving)! He would also take us to lunch at the Chino Airport in California, where we’d watch the planes land and take off. It was so much fun!

My father also took us to Chino Airport, and to the Planes of Fame Museum next door to see the B-17 ‘Piccadilly Lilly II’, the big plane like the one our grandpa flew. I have been able to share the same experience with my own kids. We now have a third-generation picture of my kids in front of the same B-17, ‘Piccadilly Lilly II’. My son liked the museum so much he asked to go again, and we took a group of his friends there for his birthday, many moons ago!

My grandfather passed away on Father’s Day, 15 June 1980. I was only 8 years old. We were very close. I didn’t understand. I never had someone close to me die before. It’s hard to understand that there will be no more hugs, or fun trips, or even just the sound of his voice. I’ll never get to hear his story, in his own words. His story IS history. I want to give him and all the other men and women who served the honor, the respect, and the chance to perhaps find closure, to heal old wounds, or to find answers to the unknown fate of some of the others who served.

To my grandfather James N. Hentges and ALL veterans:

- Thank you for your service, your love, your honor and dedication to preserving the freedoms of our great countries. May God watch over you and guide you, and may He bless each and every one of you.

- To those who gave all and made the ultimate sacrifice, please know we have not forgotten. We will continue to preserve history

and share in the memories of your lives with future generations to come. Thank you for your service. May you forever rest in peace.

|

2nd Lt. James Nicklos Hentges 338th Bomb Squadron 96th Bomb Group      My grandfather Jim Hentges was a 2nd Lt./Flight Officer and bombardier in WWII. He was born on 9th December 1923 in LeMars, Iowa, and had two brothers and one sister. At some point during his childhood, his family to Orange County, California, where he graduated from Santa Ana High School.

He enlisted with the US Army Air Corps on 11 December 1942, just two days after his 18th birthday, in Santa Ana, California. He did his preliminary training at the Santa Ana Army Air Base. His brother, William Hentges, Jr. joined the Navy and was a Seaman, 1st Class, assigned to an Amphibious Branch and stationed somewhere in the South Pacific. I am told that my grandfather completed his bombardier training at Deming Army Air Field, in Deming, New Mexico and graduated with the Class of 44-08.

I was given two photos of my grandfather by my father and was told that the plane in the photos was a training aircraft assigned to the Ardmore Army Air Field, in Ardmore, Oklahoma, which was a four engine aircraft training base. Here is information I received about the aircraft that is reportedly the one in the photos my dad gave me (I don’t know if my grandfather was at any of the following locations during his training):

- Aircraft delivered to Cheyenne AAF, Wyoming on 23/02/1944

- To Great Falls AAB in Montana on 26/02/1944

- Back to Cheyenne on 02/03/1944

- To 222 BU Ardmore on 30/08/1944

- To 332 BU Ardmore on 19/06/1945

- To 370 BU Sheppard AFB in Texas on 19/06/1945

- Back to 332 BU in Ardmore on 26/02/1945

- Sold to the Reconstruction Finance Corp. on 24/08/1945 and scrapped at Walnut Ridge AFB, Arkansas

My grandfather told my dad that they flew their planes to England, stopping in Greenland to re-fuel. He said that was the quickest route to get there. On 2 October 1944, he was assigned to the 338th Bombardment Squadron, 96th Bombardment Group (Heavy), 3rd Bombardment Division, 45th Combat Bomb Wing, 8th Air Force and stationed at Snetterton Heath Air Field (AAF Stn: 138-ETG, RCL: BX-A), known as the ‘Snetterton Falcons’ and home to everyone’s favorite mascot, Lady Moe the donkey.

I have been unable to locate information on his first 6 missions. But I do have some information on his 7th mission, which was his last. He was the bombardier on B-17G-90-BO, a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress (airplane #43-38644, nicknamed “Green Weenie”).

The winter of 1944-45 was the coldest on record in 54 years. Their target on 5 December 1944 was an ordnance plant located in Berlin, Germany. The weather was not good. With low clouds making visibility nearly impossible, and strong, changing wind gusts, it would be dangerous and difficult. Dangerous because they needed to fly lower and get under the clouds to get a good visual of their target, and, with the changing wind and weather, difficult to calculate the precise time to drop the bomb load on the specified target.

Don’t forget the hours-long flight, the tiny, cramped spaces, and crews battling exhaustion and fatigue and having to wear electric suits that at times would malfunction and catch fire. Heated gloves, if removed to help a crewman in trouble or to pull a ripcord, could mean the loss of fingers due to frostbite. And hard, heavy metal helmets that moved all around and were a struggle to keep on, and that were supposed to help your protect your head in case a bomb hits and blasts apart the aircraft, but in reality were more like a big bullet because when the blast hit, the helmet flew off your head and shot through the aircraft, leaving nothing in its wake.

Don’t forget the very important, big, bulky oxygen masks. The warplanes were not like the modern ones of today. They weren’t equipped with pressurized cabins. Those masks were a lifeline, and one little leak or a few too many minutes trying to outrun the enemy’s fire could cause you not to have enough oxygen left to complete your mission and get back to base. Dizziness, confusion, panic, and paranoia would then set in - almost always a death sentence for all aboard.

No wonder the loss of life was so great. The odds kept stacking against them. With each new mission, the odds of being able to complete the mission and make it back to base uninjured and alive became slimmer.

Based on eyewitness accounts and crew statements, my grandfather’s flight was at about 28,000 feet over their target when they started taking on lots of flak. I assume that most or all of their bomb-load was had already been dropped because somehow they were hit by flak that came in through the open bomb-bay doors and started a fire. I read that if planes were hit with full loads they would explode upon being struck, with no chance of survival. My grandfather told my dad that flak shrapnel went straight through the plane. It caused a small fire, but they quickly put it out.

But by then they were also taking on enemy fire from three German ME-109s. That’s when they got hit. They lost one engine, then two. My grandfather said they were down to one engine when they bailed out. One eyewitness stated that my grandfather’s aircraft was able to shoot down one of the ME-109s before he lost sight of the plane and its crew. Eyewitness and crew reports agree that when first hit, the aircraft appeared to be out of control. But then the pilot, David Monroe, managed somehow to regain control of the aircraft and took it straight up into the thick, dark clouds. The same clouds that once caused them danger and difficulty now provided them safety and protection from the remaining two ME-109s.

All ten crew members of my grandfather’s B-17 were able to bail out and land safely, with no one suffering from any major injuries. When asked months later, one crewman stated that the Green Weenie’s crash site was about 30 miles from Berlin, Germany. They were quickly captured by German soldiers southeast of Parchim, Germany, and taken to a POW camp called Stalag Luft 1- North 3, in Barth, Germany. Four days later, on 9 December 1944, my grandfather spent his 21st birthday (most likely in solitary confinement) awaiting interrogation by the Germans, as was customary for new prisoners. I have read that they could be in the interrogation rooms for a week to a month, or for some even longer. The Germans would try just about anything to get the men to talk.

I recently read about the conditions of Stalag Luft 1, where my grandfather and his crew were held. There were only two latrines for 2,500 men. Toward the end of the war, they received only one bowl of soup (that was mostly water) and a piece of bread per day. Bunks, if they can be called that, were so low that you couldn’t sit up on them and were stacked four high. They were each furnished with a straw-stuffed bedroll. Maybe there was a thin blanket, but never a pillow. I read that POWs called them mortuary slabs, because that’s about what they looked like.

My grandfather was one of the lucky ones since he was assigned to the officers’ section, the ‘better’ section. I can’t even begin to think what the other sections must have been like. The American commander of their barracks in the North 3 section was WWII fighter ace, Francis ‘Gabby’ Gabrowski. My grandfather told my dad he was in the same barracks with Gabby and that he was loud and arrogant as all hell!

They were finally liberated by the Russians and released on 30 April 1945. He and his crew touched US soil on 2 June 1945. Most of them, like my grandfather, had jobs to do, families to raise, and just didn’t speak much of their time in the war.

My grandpa married my grandmother, Helen Louise (Mitchell-St. Clair) Hentges in 1956. From a previous marriage, she had a son, my father (Michael St. Clair, born July 4, 1947), whom my grandfather raised as his own son. My dad never really knew his real dad, (Walter James St. Clair, also a WWII US Army Air Force veteran), because he and my grandma divorced soon after my dad was born. By the time I tracked him down, he had already passed away.

My dad is an Air Force veteran as well, and served in Vietnam. I was born at Eglin AFB in Okaloosa County, Florida. Three weeks after my birth, my mom brought us to California, where my dad joined us after being discharged from the service.

My grandpa Hentges was a wonderful grandfather! He took us fishing, horseback riding, took us to the pizza parlor and gave us pennies to ride the mechanical horse! He even met us drive his work van (well, we got to steer the van while he worked the pedals, but to us we were driving)! He would also take us to lunch at the Chino Airport in California, where we’d watch the planes land and take off. It was so much fun!

My father also took us to Chino Airport, and to the Planes of Fame Museum next door to see the B-17 ‘Piccadilly Lilly II’, the big plane like the one our grandpa flew. I have been able to share the same experience with my own kids. We now have a third-generation picture of my kids in front of the same B-17, ‘Piccadilly Lilly II’. My son liked the museum so much he asked to go again, and we took a group of his friends there for his birthday, many moons ago!

My grandfather passed away on Father’s Day, 15 June 1980. I was only 8 years old. We were very close. I didn’t understand. I never had someone close to me die before. It’s hard to understand that there will be no more hugs, or fun trips, or even just the sound of his voice. I’ll never get to hear his story, in his own words. His story IS history. I want to give him and all the other men and women who served the honor, the respect, and the chance to perhaps find closure, to heal old wounds, or to find answers to the unknown fate of some of the others who served.

To my grandfather James N. Hentges and ALL veterans:

Thank you for your service, your love, your honor and dedication to preserving the freedoms of our great countries. May God watch over you and guide you, and may He bless each and every one of you.

To those who gave all and made the ultimate sacrifice, please know we have not forgotten. We will continue to preserve history

and share in the memories of your lives with future generations to come. Thank you for your service. May you forever rest in peace.

|

Capt Harlan Bennett Bixby 351st Bomb Group Heavy Harlan Bixby served with the 351st Heavy Bomber Group US Air Force in WW2. On 31st of December 1943, his plane, the B-17 "Piccadilly Commando", ditched off the beach of Guernsey Island. Harlan was captured by the Germans and ended up in Stalag Luft 1. For the next 16 months he was incarcerated there.

|

2nd Lt. Herbert Bruce Gates 571st Bomb Squadron Herbert Gates, called Bruce by family and friends, was a 2nd Lieutenant Bombardier/Togglier. He flew 13 missions with crew 87 before being shot down by flak on the 14th mission, to Merseburg on 30th of November 1944.

Four crew members were killed that day, Pilot Edwin C. Booth, Co-Pilot Quentin L. Davidson, Ball Turret Gunner Joseph D. Jackson, and Top Turret Gunner John E. Walsh. Navigator Abraham Elhai evaded according to American Air Museum in Britain, but is listed as a POW by 390th Generations as well. Remaining crew became POWs, Waist Gunner Bruce J. Greeno, Radio Operator William P Long, Tail Gunner Anthony J. Morreale,

The aircraft, a B-17G, De Joker, was flying at about 27,000 feet at time of explosion. Bruce Gates recalled the last thing he remembered was pulling the ripcord before passing out, then he regained consciousness a few seconds before hitting the ground. Many parachutes were seen and small arms fire was prevalent. Upon hitting the ground, he ditched his parachute, saw scattered German ground forces, and ran into a ravine where he hid under brush. 3 armed German soldiers appeared at the top of the ravine, looked as though they would fire into the brush, but turned and ran away. Bruce thought they may have considered he was armed and would have shot 1 or 2 of them before they killed him. In actuality, crews had been told not to carry their .45 automatics at that time of the war, believing they would be shot on site if they were armed. He carried no weapon.

After attempting to make his way to the Allied Forces for about 10 days, sick and with no food or water, he was captured. He was held for several days in a barn, awaiting transport. He was awakened one morning by something that hit him on his cot, it was a piece of hard bread, thrown through a high window by a small boy. When he stood on the cot to see out the window, he saw the boy, and about 50 yards away, a woman, likely the boy's mother, standing on the porch of the house, looking out for visitors. The boy signalled, asking Bruce if he wanted something to drink. The boy ran to the house, retrieved a jar of what may have been peach brandy, which Bruce said was the best thing he ever drank and tasted in his life. A few days later he was taken by German soldiers to a troop train, and interrogation in Frankfurt, after which he was assigned to Stalag Luft I in Barth, Germany for the remainder of the war. Upon liberation by Russian forces in May of 1945, he was one of about 8500 POWs sent from Stalag Luft I to Camp Lucky Strike in the Le Havre, France area before transporting by ship back to the United States.

His family in Texas had been notified soon after he was shot down that he was Killed in Action.

His return was a joyous occasion, and he resided in Texas until his death at age 73.

Married for almost 50 years, he had 2 boys, 5 grandchildren, and as of this writing, 2 great-grandchildren.

|

Lt.Col. Henry Russel Spicer 362nd Fighter Squadron 357th Fighter Group Le 5 mars 1944 le nouveau commandant du 357e FG (volant avec le 362e FS), le colonel Henry Russell SPICER (1909-1968), fut touché par la Flak au retour d’une mission sur Bordeaux et son P-51 "Tony Boy" en feu, se parachuta au dessus de la Manche à une quinzaine de kilomètres de la côte à hauteur du Havre. Après avoir dérivé sur son dinghy pendant deux jours, il fut capturé à Cherbourg, pieds et mains gelés, et envoyé au Stalag Luft 1 de Barth-Vogelsand. Il décéda à 59 ans.

On 5th of March 1944 the new commander of the 357th Fighter Group, flying with the 362nd Fighter Squadron, Colonel Henry Russell Spicer was hit by the Flak on the return of a mission on Bordeaux and his P-51 Tony Boy. On fire, he parachuted over the English Channel about fifteen kilometers from the coast at Le Havre. After drifting on his dinghy for two days, he was captured in Cherbourg, with frozen feet and hands and sent to Stalag Luft 1 of Barth-Vogelsand. He died at age of 59.

|

Flt/O. R C Saunders 76 Squadron Pilot Officer W. J. Morgan was the flight engineer in LK687 Halifax V, from 76 squadron based at Holme on Spaulding Moor. The plane was shot down on a raid to Stuttgart at 17.01hrs on 26th November 1943 and crashed at Retzbach. The Pilot and rear gunner both died and are buried at Durnbach War Cemetery, the remaining 5 crew members were captured and became Prisoners of War.

|

P/O J R Rogers 76 Squadron Pilot Officer W. J. Morgan was the flight engineer in LK687 Halifax V, from 76 squadron based at Holme on Spaulding Moor. The plane was shot down on a raid to Stuttgart at 17.01hrs on 26th November 1943 and crashed at Retzbach. The Pilot and rear gunner both died and are buried at Durnbach War Cemetery, the remaining 5 crew members were captured and became Prisoners of War

|

P/O H R W Whittle 76 Squadron (d.26th November 1943) Pilot Officer W. J. Morgan was the flight engineer in LK687 Halifax V, from 76 squadron based at Holme on Spaulding Moor. The plane was shot down on a raid to Stuttgart at 17.01hrs on 26th November 1943 and crashed at Retzbach. The Pilot and rear gunner both died and are buried at Durnbach War Cemetery, the remaining 5 crew members were captured and became Prisoners of War. Crew:- - Pilot officer H R W Whittle, Died.

- Pilot Officer W J Morgan,captured POW.

- Pilot Officer J R Rogers, captured POW.

- Flight Sergeant J A A Roy, Royal Canadian Air Force, captured POW.

- Flight Officer R C Saunders, captured POW.

- Sergeant W Coates, captured POW.

- Sergeant F A MacPhersonm Died.

|

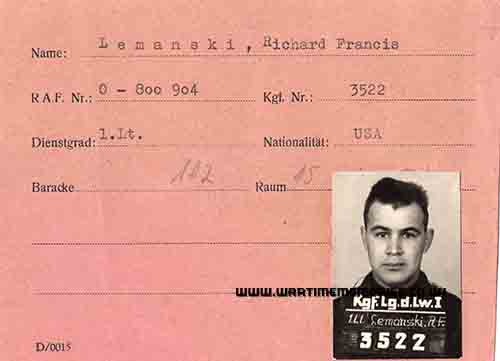

1st.Lt. Richard F. Lemanski 339th Bomb Squadron 69th Bomb Group 1st Lt. Richard Lemanski completed 11 missions to Ludwigshaven, Brunswick, Wilhelmshaven, Frankfort, Rostock, Poznan, Belgium, French and Polish objectives. He was shot down by ME 109s on the mission to Berlin on 8th March 1944 Mission #252 in B-17 #4231576. Richard spent his 20th and 21st birthdays during fourteen months as a Prisoner of War in Stalag Luft 1 in Barth, Germany, room 15 Block 2. He was the youngest pilot in the 96th Bomb Group and probably in the 8th AF. Although some were seriously injured, all crew members survived to return home safely. The crew was credited with many fighter kills.

|

F/Lt. George W. Gardiner 429 Squadron My dad, George Gardiner was on his 23 mission on July 18th 1944 when his plane was hit from falling bombs from above Aircraft Halifax LW127. Went down 3 killed 3 POW's and 1 made it back to friendly lines. Phil Brunet was in the same camp and bunk house.

|

Sgt. Clifford Webb MBE. 21 Squadron We believe that my father Clifford Webb was captured twice.

This article was found which was probably written by our father to his mother after the second capture/escape. If anybody can shed some light on Clifford Webb, it would certainly be most appreciated !

The article Letter home from Sgt. C. Webb, RAF, from “Woodside”, Homer, aged 24 years. C. 1940.

We were shot down in France, near Calais, on June 14th, by six Messerschmitts, but nobody was injured, so we tried to make our way back to England. We found a little boat three days after the crash, but had no chance to stock it with food and drink.

Our oars were very weak and soon broke. The upshot of it all was that we were in the channel for three days without food or drink and not a stitch of dry clothing on us. One of my companions died on the last night and the two of us left were washed back on the French coast, still behind the German lines.

We hid for two days to regain our strength, and started walking to Le Havre about 50 miles away, but abandoned the idea as the port was too closely watched. Then we tried to get work on the farms, posing as Belgians, but failed because we had no identification papers. We begged bought and stole food and civilian clothing during this time.

Eventually we decided to go north and try to cross the Channel again, but were unlucky enough to walk into a hidden German aerodrome, just south of the Somme. We were stopped and questioned; I was the only one speaking French. They found out my companion was English so I was taken as well. This was on the evening of July 1st.

I don’t know how I escaped, but all the people in this camp are the same. Some of the escapees from crashes are nothing short of miraculous.

Report of incident near Calais.

14/06/1940: Merville, France.

- Type: Bristol Type 142L, Blenheim Mk. IV

- Serial number: R3742,YH-?

- Operation: Merville

- Lost: 14/06/1940

- Pilot Officer William A. Saunders, RAF 40756, 21 Sqn., age 20, 14/06/1940, missing

- Sgt W.H.Eden PoW also initialled H.W.Eden

- Sgt C.Webb PoW

- Airborne from Bodney. Crash-site not established. Last seen being chased by Me109s.

- P/O Saunders has no known grave and is commemorated on the Runnymede Mmemorial.

- Sgt W.H.Eden on his 30th operation evaded until captured July 40 near Doullens after spending 3 days in a rowing boat and interned in Camps L1/L6/357, PoW No.87.

- Sgt C.Webb was also captured with his comrade but was interned in Camps L1/L3/L6/357, PoW No.76.

|

Fred W. Butler I was a POW at Stalag Luft 1 Barth from Feb 1944 to May 1945 and was one of twelve "Kriegies" who decided to walk to freedom and out of Germany from North Compound I. I was accompanied by Harry Korger, Bill Reichle and Bill Dallas to name a few. The rest of the names escape me. It was after the Russians had arrived and they helped us by ferrying us to the mainland by boat two at a time. I'm trying to remember the whole story.

|

W/O L. W. C. Lewis 514 Sqd. W/O Lewis survived the loss of Lancaster DS822 JI-T when it came down at La Celle Le Bordes France on the 8th of June 1944 whilst on a bombing raid to Massy Palaiseau. He evaded capture until the 16th of August and was then taken to Stalag 12a and later to Stalag Luft 1.

|

Wing Cdr. William David Gordon-Watkins DSO DFC DFM 15 Sqd Wing Cmdr Gordon-Watkins was the Commanding Officer of 15 Sqd. He was shot down on the 16th of November 1944 whilst piloting the lead bomber on a mission to Heinsburg. He was the only member of the crew to survive the incident and was captured and held as a prisoner of war in Stalag Luft 1. He had completed over 50 operations and had previously served with 149 sqd.

|

Sgt. Douglas Wilmott Waters No. 214 Squadron Douglas Waters flew with No. 214 Squadron, he was held as a Prisoner of War in Stalag Luft 1.

|

F/O. James Nicholas Hentges 338th Bombardment Sqdn. 96th Bombardment Group      My grandfather Jim was a 2nd Lt./Flight Officer and bombardier in WWII. He was born on 9 December 1923 in LeMars, Iowa, and had two brothers and one sister. At some point during his childhood, his family to Orange County, California, where he graduated from Santa Ana High School.

He enlisted with the US Army Air Corps on 11 December 1942, just two days after his 18th birthday, in Santa Ana, California. He did his preliminary training at the Santa Ana Army Air Base. His brother, William Hentges, Jr. joined the Navy and was a Seaman, 1st Class, assigned to an Amphibious Branch and stationed somewhere in the South Pacific. I am told that my grandfather completed his bombardier training at Deming Army Air Field, in Deming, New Mexico and graduated with the Class of 44-08.

I was given two photos of my grandfather by my father and was told that the plane in the photos was a training aircraft assigned to the Ardmore Army Air Field, in Ardmore, Oklahoma, which was a four engine aircraft training base. Here is information I received about the aircraft that is reportedly the one in the photos my dad gave me (I don’t know if my grandfather was at any of the following locations during his training):

- Aircraft delivered to Cheyenne AAF, Wyoming on 23/02/1944

- To Great Falls AAB in Montana on 26/02/1944

- Back to Cheyenne on 02/03/1944

- To 222 BU Ardmore on 30/08/1944

- To 332 BU Ardmore on 19/06/1945

- To 370 BU Sheppard AFB in Texas on 19/06/1945

- Back to 332 BU in Ardmore on 26/02/1945

- Sold to the Reconstruction Finance Corp. on 24/08/1945 and scrapped at Walnut Ridge AFB, Arkansas

My grandfather told my dad that they flew their planes to England, stopping in Greenland to re-fuel. He said that was the quickest route to get there. On 2 October 1944, he was assigned to the 338th Bombardment Squadron, 96th Bombardment Group (Heavy), 3rd Bombardment Division, 45th Combat Bomb Wing, 8th Air Force and stationed at Snetterton Heath Air Field (AAF Stn: 138-ETG, RCL: BX-A), known as the ‘Snetterton Falcons’ and home to everyone’s favorite mascot, Lady Moe the donkey.

I have been unable to locate information on his first 6 missions. But I do have some information on his 7th mission, which was his last. He was the bombardier on B-17G-90-BO, a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress (airplane #43-38644, nicknamed “Green Weenie”).

The winter of 1944-45 was the coldest on record in 54 years. Their target on 5 December 1944 was an ordnance plant located in Berlin, Germany. The weather was not good. With low clouds making visibility nearly impossible, and strong, changing wind gusts, it would be dangerous and difficult. Dangerous because they needed to fly lower and get under the clouds to get a good visual of their target, and, with the changing wind and weather, difficult to calculate the precise time to drop the bomb load on the specified target.

Don’t forget the hours-long flight, the tiny, cramped spaces, and crews battling exhaustion and fatigue and having to wear electric suits that at times would malfunction and catch fire. Heated gloves, if removed to help a crewman in trouble or to pull a ripcord, could mean the loss of fingers due to frostbite. And hard, heavy metal helmets that moved all around and were a struggle to keep on, and that were supposed to help your protect your head in case a bomb hits and blasts apart the aircraft, but in reality were more like a big bullet because when the blast hit, the helmet flew off your head and shot through the aircraft, leaving nothing in its wake.

Don’t forget the very important, big, bulky oxygen masks. The warplanes were not like the modern ones of today. They weren’t equipped with pressurized cabins. Those masks were a lifeline, and one little leak or a few too many minutes trying to outrun the enemy’s fire could cause you not to have enough oxygen left to complete your mission and get back to base. Dizziness, confusion, panic, and paranoia would then set in - almost always a death sentence for all aboard.

No wonder the loss of life was so great. The odds kept stacking against them. With each new mission, the odds of being able to complete the mission and make it back to base uninjured and alive became slimmer.

Based on eyewitness accounts and crew statements, my grandfather’s flight was at about 28,000 feet over their target when they started taking on lots of flak. I assume that most or all of their bomb-load was had already been dropped because somehow they were hit by flak that came in through the open bomb-bay doors and started a fire. I read that if planes were hit with full loads they would explode upon being struck, with no chance of survival. My grandfather told my dad that flak shrapnel went straight through the plane. It caused a small fire, but they quickly put it out.

But by then they were also taking on enemy fire from three German ME-109s. That’s when they got hit. They lost one engine, then two. My grandfather said they were down to one engine when they bailed out. One eyewitness stated that my grandfather’s aircraft was able to shoot down one of the ME-109s before he lost sight of the plane and its crew. Eyewitness and crew reports agree that when first hit, the aircraft appeared to be out of control. But then the pilot, David Monroe, managed somehow to regain control of the aircraft and took it straight up into the thick, dark clouds. The same clouds that once caused them danger and difficulty now provided them safety and protection from the remaining two ME-109s.

All ten crew members of my grandfather’s B-17 were able to bail out and land safely, with no one suffering from any major injuries. When asked months later, one crewman stated that the Green Weenie’s crash site was about 30 miles from Berlin, Germany. They were quickly captured by German soldiers southeast of Parchim, Germany, and taken to a POW camp called Stalag Luft 1- North 3, in Barth, Germany. Four days later, on 9 December 1944, my grandfather spent his 21st birthday (most likely in solitary confinement) awaiting interrogation by the Germans, as was customary for new prisoners. I have read that they could be in the interrogation rooms for a week to a month, or for some even longer. The Germans would try just about anything to get the men to talk.

I recently read about the conditions of Stalag Luft 1, where my grandfather and his crew were held. There were only two latrines for 2,500 men. Toward the end of the war, they received only one bowl of soup (that was mostly water) and a piece of bread per day. Bunks, if they can be called that, were so low that you couldn’t sit up on them and were stacked four high. They were each furnished with a straw-stuffed bedroll. Maybe there was a thin blanket, but never a pillow. I read that POWs called them mortuary slabs, because that’s about what they looked like.

My grandfather was one of the lucky ones since he was assigned to the officers’ section, the ‘better’ section. I can’t even begin to think what the other sections must have been like. The American commander of their barracks in the North 3 section was WWII fighter ace, Francis ‘Gabby’ Gabrowski. My grandfather told my dad he was in the same barracks with Gabby and that he was loud and arrogant as all hell!

They were finally liberated by the Russians and released on 30 April 1945. He and his crew touched US soil on 2 June 1945. Most of them, like my grandfather, had jobs to do, families to raise, and just didn’t speak much of their time in the war.

My grandpa married my grandmother, Helen Louise (Mitchell-St. Clair) Hentges in 1956. From a previous marriage, she had a son, my father (Michael St. Clair, born July 4, 1947), whom my grandfather raised as his own son. My dad never really knew his real dad, (Walter James St. Clair, also a WWII US Army Air Force veteran), because he and my grandma divorced soon after my dad was born. By the time I tracked him down, he had already passed away.

My dad is an Air Force veteran as well, and served in Vietnam. I was born at Eglin AFB in Okaloosa County, Florida. Three weeks after my birth, my mom brought us to California, where my dad joined us after being discharged from the service.

My grandpa Hentges was a wonderful grandfather! He took us fishing, horseback riding, took us to the pizza parlor and gave us pennies to ride the mechanical horse! He even met us drive his work van (well, we got to steer the van while he worked the pedals, but to us we were driving)! He would also take us to lunch at the Chino Airport in California, where we’d watch the planes land and take off. It was so much fun!

My father also took us to Chino Airport, and to the Planes of Fame Museum next door to see the B-17 ‘Piccadilly Lilly II’, the big plane like the one our grandpa flew. I have been able to share the same experience with my own kids. We now have a third-generation picture of my kids in front of the same B-17, ‘Piccadilly Lilly II’. My son liked the museum so much he asked to go again, and we took a group of his friends there for his birthday, many moons ago!

My grandfather passed away on Father’s Day, 15 June 1980. I was only 8 years old. We were very close. I didn’t understand. I never had someone close to me die before. It’s hard to understand that there will be no more hugs, or fun trips, or even just the sound of his voice. I’ll never get to hear his story, in his own words. His story IS history. I want to give him and all the other men and women who served the honor, the respect, and the chance to perhaps find closure, to heal old wounds, or to find answers to the unknown fate of some of the others who served.

To my grandfather James N. Hentges and ALL veterans:

- Thank you for your service, your love, your honor and dedication to preserving the freedoms of our great countries. May God watch over you and guide you, and may He bless each and every one of you.

- To those who gave all and made the ultimate sacrifice, please know we have not forgotten. We will continue to preserve history

and share in the memories of your lives with future generations to come. Thank you for your service. May you forever rest in peace.

|

2nd Lt. James Nicklos Hentges 338th Bomb Squadron 96th Bomb Group      My grandfather Jim Hentges was a 2nd Lt./Flight Officer and bombardier in WWII. He was born on 9th December 1923 in LeMars, Iowa, and had two brothers and one sister. At some point during his childhood, his family to Orange County, California, where he graduated from Santa Ana High School.

He enlisted with the US Army Air Corps on 11 December 1942, just two days after his 18th birthday, in Santa Ana, California. He did his preliminary training at the Santa Ana Army Air Base. His brother, William Hentges, Jr. joined the Navy and was a Seaman, 1st Class, assigned to an Amphibious Branch and stationed somewhere in the South Pacific. I am told that my grandfather completed his bombardier training at Deming Army Air Field, in Deming, New Mexico and graduated with the Class of 44-08.

I was given two photos of my grandfather by my father and was told that the plane in the photos was a training aircraft assigned to the Ardmore Army Air Field, in Ardmore, Oklahoma, which was a four engine aircraft training base. Here is information I received about the aircraft that is reportedly the one in the photos my dad gave me (I don’t know if my grandfather was at any of the following locations during his training):

- Aircraft delivered to Cheyenne AAF, Wyoming on 23/02/1944

- To Great Falls AAB in Montana on 26/02/1944

- Back to Cheyenne on 02/03/1944

- To 222 BU Ardmore on 30/08/1944

- To 332 BU Ardmore on 19/06/1945

- To 370 BU Sheppard AFB in Texas on 19/06/1945

- Back to 332 BU in Ardmore on 26/02/1945

- Sold to the Reconstruction Finance Corp. on 24/08/1945 and scrapped at Walnut Ridge AFB, Arkansas

My grandfather told my dad that they flew their planes to England, stopping in Greenland to re-fuel. He said that was the quickest route to get there. On 2 October 1944, he was assigned to the 338th Bombardment Squadron, 96th Bombardment Group (Heavy), 3rd Bombardment Division, 45th Combat Bomb Wing, 8th Air Force and stationed at Snetterton Heath Air Field (AAF Stn: 138-ETG, RCL: BX-A), known as the ‘Snetterton Falcons’ and home to everyone’s favorite mascot, Lady Moe the donkey.

I have been unable to locate information on his first 6 missions. But I do have some information on his 7th mission, which was his last. He was the bombardier on B-17G-90-BO, a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress (airplane #43-38644, nicknamed “Green Weenie”).

The winter of 1944-45 was the coldest on record in 54 years. Their target on 5 December 1944 was an ordnance plant located in Berlin, Germany. The weather was not good. With low clouds making visibility nearly impossible, and strong, changing wind gusts, it would be dangerous and difficult. Dangerous because they needed to fly lower and get under the clouds to get a good visual of their target, and, with the changing wind and weather, difficult to calculate the precise time to drop the bomb load on the specified target.

Don’t forget the hours-long flight, the tiny, cramped spaces, and crews battling exhaustion and fatigue and having to wear electric suits that at times would malfunction and catch fire. Heated gloves, if removed to help a crewman in trouble or to pull a ripcord, could mean the loss of fingers due to frostbite. And hard, heavy metal helmets that moved all around and were a struggle to keep on, and that were supposed to help your protect your head in case a bomb hits and blasts apart the aircraft, but in reality were more like a big bullet because when the blast hit, the helmet flew off your head and shot through the aircraft, leaving nothing in its wake.

Don’t forget the very important, big, bulky oxygen masks. The warplanes were not like the modern ones of today. They weren’t equipped with pressurized cabins. Those masks were a lifeline, and one little leak or a few too many minutes trying to outrun the enemy’s fire could cause you not to have enough oxygen left to complete your mission and get back to base. Dizziness, confusion, panic, and paranoia would then set in - almost always a death sentence for all aboard.

No wonder the loss of life was so great. The odds kept stacking against them. With each new mission, the odds of being able to complete the mission and make it back to base uninjured and alive became slimmer.

Based on eyewitness accounts and crew statements, my grandfather’s flight was at about 28,000 feet over their target when they started taking on lots of flak. I assume that most or all of their bomb-load was had already been dropped because somehow they were hit by flak that came in through the open bomb-bay doors and started a fire. I read that if planes were hit with full loads they would explode upon being struck, with no chance of survival. My grandfather told my dad that flak shrapnel went straight through the plane. It caused a small fire, but they quickly put it out.

But by then they were also taking on enemy fire from three German ME-109s. That’s when they got hit. They lost one engine, then two. My grandfather said they were down to one engine when they bailed out. One eyewitness stated that my grandfather’s aircraft was able to shoot down one of the ME-109s before he lost sight of the plane and its crew. Eyewitness and crew reports agree that when first hit, the aircraft appeared to be out of control. But then the pilot, David Monroe, managed somehow to regain control of the aircraft and took it straight up into the thick, dark clouds. The same clouds that once caused them danger and difficulty now provided them safety and protection from the remaining two ME-109s.

All ten crew members of my grandfather’s B-17 were able to bail out and land safely, with no one suffering from any major injuries. When asked months later, one crewman stated that the Green Weenie’s crash site was about 30 miles from Berlin, Germany. They were quickly captured by German soldiers southeast of Parchim, Germany, and taken to a POW camp called Stalag Luft 1- North 3, in Barth, Germany. Four days later, on 9 December 1944, my grandfather spent his 21st birthday (most likely in solitary confinement) awaiting interrogation by the Germans, as was customary for new prisoners. I have read that they could be in the interrogation rooms for a week to a month, or for some even longer. The Germans would try just about anything to get the men to talk.

I recently read about the conditions of Stalag Luft 1, where my grandfather and his crew were held. There were only two latrines for 2,500 men. Toward the end of the war, they received only one bowl of soup (that was mostly water) and a piece of bread per day. Bunks, if they can be called that, were so low that you couldn’t sit up on them and were stacked four high. They were each furnished with a straw-stuffed bedroll. Maybe there was a thin blanket, but never a pillow. I read that POWs called them mortuary slabs, because that’s about what they looked like.

My grandfather was one of the lucky ones since he was assigned to the officers’ section, the ‘better’ section. I can’t even begin to think what the other sections must have been like. The American commander of their barracks in the North 3 section was WWII fighter ace, Francis ‘Gabby’ Gabrowski. My grandfather told my dad he was in the same barracks with Gabby and that he was loud and arrogant as all hell!

They were finally liberated by the Russians and released on 30 April 1945. He and his crew touched US soil on 2 June 1945. Most of them, like my grandfather, had jobs to do, families to raise, and just didn’t speak much of their time in the war.

My grandpa married my grandmother, Helen Louise (Mitchell-St. Clair) Hentges in 1956. From a previous marriage, she had a son, my father (Michael St. Clair, born July 4, 1947), whom my grandfather raised as his own son. My dad never really knew his real dad, (Walter James St. Clair, also a WWII US Army Air Force veteran), because he and my grandma divorced soon after my dad was born. By the time I tracked him down, he had already passed away.

My dad is an Air Force veteran as well, and served in Vietnam. I was born at Eglin AFB in Okaloosa County, Florida. Three weeks after my birth, my mom brought us to California, where my dad joined us after being discharged from the service.

My grandpa Hentges was a wonderful grandfather! He took us fishing, horseback riding, took us to the pizza parlor and gave us pennies to ride the mechanical horse! He even met us drive his work van (well, we got to steer the van while he worked the pedals, but to us we were driving)! He would also take us to lunch at the Chino Airport in California, where we’d watch the planes land and take off. It was so much fun!

My father also took us to Chino Airport, and to the Planes of Fame Museum next door to see the B-17 ‘Piccadilly Lilly II’, the big plane like the one our grandpa flew. I have been able to share the same experience with my own kids. We now have a third-generation picture of my kids in front of the same B-17, ‘Piccadilly Lilly II’. My son liked the museum so much he asked to go again, and we took a group of his friends there for his birthday, many moons ago!

My grandfather passed away on Father’s Day, 15 June 1980. I was only 8 years old. We were very close. I didn’t understand. I never had someone close to me die before. It’s hard to understand that there will be no more hugs, or fun trips, or even just the sound of his voice. I’ll never get to hear his story, in his own words. His story IS history. I want to give him and all the other men and women who served the honor, the respect, and the chance to perhaps find closure, to heal old wounds, or to find answers to the unknown fate of some of the others who served.

To my grandfather James N. Hentges and ALL veterans:

Thank you for your service, your love, your honor and dedication to preserving the freedoms of our great countries. May God watch over you and guide you, and may He bless each and every one of you.

To those who gave all and made the ultimate sacrifice, please know we have not forgotten. We will continue to preserve history

and share in the memories of your lives with future generations to come. Thank you for your service. May you forever rest in peace.

|

Capt Harlan Bennett Bixby 351st Bomb Group Heavy Harlan Bixby served with the 351st Heavy Bomber Group US Air Force in WW2. On 31st of December 1943, his plane, the B-17 "Piccadilly Commando", ditched off the beach of Guernsey Island. Harlan was captured by the Germans and ended up in Stalag Luft 1. For the next 16 months he was incarcerated there.

|

2nd Lt. Herbert Bruce Gates 571st Bomb Squadron Herbert Gates, called Bruce by family and friends, was a 2nd Lieutenant Bombardier/Togglier. He flew 13 missions with crew 87 before being shot down by flak on the 14th mission, to Merseburg on 30th of November 1944.

Four crew members were killed that day, Pilot Edwin C. Booth, Co-Pilot Quentin L. Davidson, Ball Turret Gunner Joseph D. Jackson, and Top Turret Gunner John E. Walsh. Navigator Abraham Elhai evaded according to American Air Museum in Britain, but is listed as a POW by 390th Generations as well. Remaining crew became POWs, Waist Gunner Bruce J. Greeno, Radio Operator William P Long, Tail Gunner Anthony J. Morreale,

The aircraft, a B-17G, De Joker, was flying at about 27,000 feet at time of explosion. Bruce Gates recalled the last thing he remembered was pulling the ripcord before passing out, then he regained consciousness a few seconds before hitting the ground. Many parachutes were seen and small arms fire was prevalent. Upon hitting the ground, he ditched his parachute, saw scattered German ground forces, and ran into a ravine where he hid under brush. 3 armed German soldiers appeared at the top of the ravine, looked as though they would fire into the brush, but turned and ran away. Bruce thought they may have considered he was armed and would have shot 1 or 2 of them before they killed him. In actuality, crews had been told not to carry their .45 automatics at that time of the war, believing they would be shot on site if they were armed. He carried no weapon.

After attempting to make his way to the Allied Forces for about 10 days, sick and with no food or water, he was captured. He was held for several days in a barn, awaiting transport. He was awakened one morning by something that hit him on his cot, it was a piece of hard bread, thrown through a high window by a small boy. When he stood on the cot to see out the window, he saw the boy, and about 50 yards away, a woman, likely the boy's mother, standing on the porch of the house, looking out for visitors. The boy signalled, asking Bruce if he wanted something to drink. The boy ran to the house, retrieved a jar of what may have been peach brandy, which Bruce said was the best thing he ever drank and tasted in his life. A few days later he was taken by German soldiers to a troop train, and interrogation in Frankfurt, after which he was assigned to Stalag Luft I in Barth, Germany for the remainder of the war. Upon liberation by Russian forces in May of 1945, he was one of about 8500 POWs sent from Stalag Luft I to Camp Lucky Strike in the Le Havre, France area before transporting by ship back to the United States.

His family in Texas had been notified soon after he was shot down that he was Killed in Action.

His return was a joyous occasion, and he resided in Texas until his death at age 73.

Married for almost 50 years, he had 2 boys, 5 grandchildren, and as of this writing, 2 great-grandchildren.

|

Lt.Col. Henry Russel Spicer 362nd Fighter Squadron 357th Fighter Group Le 5 mars 1944 le nouveau commandant du 357e FG (volant avec le 362e FS), le colonel Henry Russell SPICER (1909-1968), fut touché par la Flak au retour d’une mission sur Bordeaux et son P-51 "Tony Boy" en feu, se parachuta au dessus de la Manche à une quinzaine de kilomètres de la côte à hauteur du Havre. Après avoir dérivé sur son dinghy pendant deux jours, il fut capturé à Cherbourg, pieds et mains gelés, et envoyé au Stalag Luft 1 de Barth-Vogelsand. Il décéda à 59 ans.

On 5th of March 1944 the new commander of the 357th Fighter Group, flying with the 362nd Fighter Squadron, Colonel Henry Russell Spicer was hit by the Flak on the return of a mission on Bordeaux and his P-51 Tony Boy. On fire, he parachuted over the English Channel about fifteen kilometers from the coast at Le Havre. After drifting on his dinghy for two days, he was captured in Cherbourg, with frozen feet and hands and sent to Stalag Luft 1 of Barth-Vogelsand. He died at age of 59.

|

Flt/O. R C Saunders 76 Squadron Pilot Officer W. J. Morgan was the flight engineer in LK687 Halifax V, from 76 squadron based at Holme on Spaulding Moor. The plane was shot down on a raid to Stuttgart at 17.01hrs on 26th November 1943 and crashed at Retzbach. The Pilot and rear gunner both died and are buried at Durnbach War Cemetery, the remaining 5 crew members were captured and became Prisoners of War.

|

P/O J R Rogers 76 Squadron Pilot Officer W. J. Morgan was the flight engineer in LK687 Halifax V, from 76 squadron based at Holme on Spaulding Moor. The plane was shot down on a raid to Stuttgart at 17.01hrs on 26th November 1943 and crashed at Retzbach. The Pilot and rear gunner both died and are buried at Durnbach War Cemetery, the remaining 5 crew members were captured and became Prisoners of War

|

P/O H R W Whittle 76 Squadron (d.26th November 1943) Pilot Officer W. J. Morgan was the flight engineer in LK687 Halifax V, from 76 squadron based at Holme on Spaulding Moor. The plane was shot down on a raid to Stuttgart at 17.01hrs on 26th November 1943 and crashed at Retzbach. The Pilot and rear gunner both died and are buried at Durnbach War Cemetery, the remaining 5 crew members were captured and became Prisoners of War. Crew:- - Pilot officer H R W Whittle, Died.

- Pilot Officer W J Morgan,captured POW.

- Pilot Officer J R Rogers, captured POW.

- Flight Sergeant J A A Roy, Royal Canadian Air Force, captured POW.

- Flight Officer R C Saunders, captured POW.

- Sergeant W Coates, captured POW.

- Sergeant F A MacPhersonm Died.

|

1st.Lt. Richard F. Lemanski 339th Bomb Squadron 69th Bomb Group 1st Lt. Richard Lemanski completed 11 missions to Ludwigshaven, Brunswick, Wilhelmshaven, Frankfort, Rostock, Poznan, Belgium, French and Polish objectives. He was shot down by ME 109s on the mission to Berlin on 8th March 1944 Mission #252 in B-17 #4231576. Richard spent his 20th and 21st birthdays during fourteen months as a Prisoner of War in Stalag Luft 1 in Barth, Germany, room 15 Block 2. He was the youngest pilot in the 96th Bomb Group and probably in the 8th AF. Although some were seriously injured, all crew members survived to return home safely. The crew was credited with many fighter kills.

|

Recomended Reading.Available at discounted prices.

|

Footprints on the Sands of Time: RAF Bomber Command Prisoners of War in Germany 1939-45Oliver Clutton-Brock

he first part of this book deals with German PoW camps as they were opened, in chronological order and to which the Bomber Command PoWs were sent. Each chapter includes anecdotes and stories of the men in the camps - capture, escape, illness, murder and more - and illustrates the awfulness of captivity even in German hands. Roughly one in every 20 captured airmen never returned home. The first part of the book also covers subjects such as how the PoWs were repatriated during the war; how they returned at war's end; the RAF traitors; the war crimes; and the vital role of the Red Cross. The style is part reference, part narrative and aims to correct many historical inaccuracies. It also includes previously unpublished photographs. The second part comprises an annotated list of all 10,995 RAF Bomber Command airmen who were taken prisoner, together with an extended introduction. The book provides an important contribution to our knowledge of the war. It is a reference work not only for the

|

|

|