F/Lt. Herbert Lindsay "Monk" Reynolds

Royal Canadian Air Force 37 Squadron

from:Montreal, Quebec

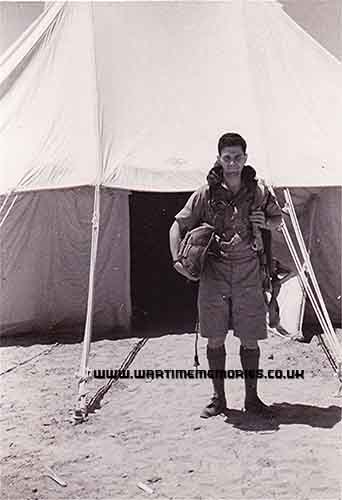

Lindsay Reynolds or Monk as he was known to his crew, enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force in November 1940. Following BCATP training as an Observer in western Canada he set sail for Britain in August 1931. He was assigned to No. 22 OTU at Wellesbourne. Later he was sent to the Middle East. Having sufficient flying time to his credit he and his crew left for Gibraltar from Overseas Air Dispatch Unit, Portreath on 23 March 1942 aboard Wellington aircraft DV517B.

On 31 March the crew were briefed for their six hour and fifty-two minute flight to Malta. Less than two hours after take they were in trouble. Fuel consumption was down. They knew they had to return to Gibraltar. Lindsay launched a ``sea marker`` to get a better reading on wind velocity and direction. On their descent into Gibraltar they flew over a merchant convoy of fifteen ships. Attempting to line up over the runway, they knew it was going to be rough landing. Just prior to crashing Lindsay braced himself with the insteps of both feet against the main spar of the aircraft. The plane crashed on landing and collided with two spitfires. Everything went up in flames, but the crew were able to escape the wreckage. The pilot, P/O Norman Knight was severely traumatized and was quickly removed from the rest of the crew. All the crew were badly shaken up. Lindsay had broken a bone in his foot but decided not to mention it to the medical officer for fear that he would be held back from operations. The crew returned to England aboard the Llanstephan Castle in search of another plane. They did no flying during April and May 1942. Lindsay was showing signs of PTSD, feeling anxious and struggling to concentrate. “After our accident the M.O. seemed to think it quite natural to be so affected but I do wish I could feel more at ease than I do. To rest is utterly impossible, and I dread the thought of flying again…I also find it so hard to study…sometimes I find myself reading and reading and not getting a thing out of it…” (Letter from Lindsay to his brother Arnold, 21 May 1942).

During the last week at Hartwell the crew was assigned another pilot, P/O Sgt. Mackenzie – a Canadian. On 6 June the crew flew to Gibraltar aboard Wellington DV652V. They left Gibraltar for Malta the next day, arriving on the same day as Canada’s Ace, “Daredevil” George Beurling. The crew landed at 21:35 local time. The plan was to refuel as quickly as possible. While refuelling took place the crew was briefed on the next leg of their journey to Egypt. They were informed that they would be transporting civilians – the wife and two children of an officer. Suddenly the briefing was interrupted by a bombing raid. It was imperative that the plane get airborne before it was hit and put out of action. Interrupting the briefing, and rushing to the plane with their precious cargo, they boarded and lined up for take off. The two Wellingtons ahead of them were hit as they attempted to get airborne. Now Lindsay’s crew had slightly less runway to work with and Sgt. Mackenzie, giving it all he had, managed to get airborne avoiding the enflamed wreckage at the end of the runway at Luqa airstrip. They had escaped the bombing, and quickly Lindsay navigated their course away from the enemy airplanes over the skies of Malta. Ninety minutes later they were recalled to Malta. At 01:45 on 10 June they landed at Luqa airfield for the second time in five hours. The fires of bombed and burned wreckage were all around the airfield illuminating the night sky, and the acrid smell of jet fuel and chemicals filled the air. It was a frightening sight. Their passenger, the mother of the two children, had not been informed that they were returning to Malta. She thought she had escaped the nightmare, only to find that she had returned to it. Upon learning of her whereabouts she burst into tears.

The crew spent two eventful days on Malta. During this time Lindsay did a shift as acting air traffic controller at Luqa. He experienced another “first.” Up until that point he had only attended military funerals, but on Malta, because he was “a religious man,” he was required to perform the burial service of a fellow airman killed in the bombing the night before since there was no available padre. At twenty-two years of age, with only the New Testament that he carried in his breast pocket, he dutifully performed his sacred duty. The next day the crew was walking over open ground on their way to Veletta. Just as they reached the middle of the field, out of nowhere came a German fighter pilot swooping down to fire on the airmen in the field. They were like ducks in a barrel. The German pilot came low enough to look into the faces of the airmen,andt to their great surprise and overwhelming relief, rather than firing on them he signalled with his finger and flew off. He could have gunned them down with the push of his thumb, but didn’t have the stomach for it.

The crew arrived at the RAF station at El-Daba, Egypt on 12 June 1942. While at El-Daba the crew was broken up and ordered to different squadrons. Lindsay was ordered to report to 37 Squadron RAF at Abu Sueir. He arrived at Abu Sueir on 30 June. Lindsay’s first night of operations was 8 July 1942. Wellington AD645H was airborne by 22:30 (local time), and Lindsay navigated the plane to the Target – Tobruk. The captain announced that the target was dead ahead and ordered him forward to prepare for the bomb run. He lay on the padded inside panel of the entry hatch to drop his bombs. He heard the pilot say he could see fires in the dock area and some bursting flak. Lindsay called out the approach bearings for the bomb run to the captain, who confirmed he had opened the bomb doors. He flipped his toggles on the bomb panel to arm the bomb. On the final approach he called out course corrections with “left, left…right, left…Hold it, steady, steady…bombs gone!” With that cry from Lindsay Pilot Officer Dudley threw the aircraft into a rather violent bank to port. The interior of the aircraft was suddenly lit up in the orange flash of exploding shells. Suddenly the sky lit up. They were caught in the search lights of the German ground forces. The crew heard the unmistakable sound of flak, too close for comfort. Their skilled and seasoned pilot suddenly took the most violent evasive action, putting the aircraft into a nose dive in an attempt to avoid the enemy search lights. He continued to dive while the crew hung on for dear life. The Wellington vibrated and shook, and all but broke apart as they descended at this accelerated pace. Pilot Officer Dudley then attempted to pull out of the dive. He pulled back on the control column or stick. Nothing happened. The gravitational force was too great. He tried again, and this time he put both feet on the instrument panel and pulled, using the full weight of his body. He was unable to muster enough strength on his own to overcome the gravitational force of the dive. Dudley shouted at the second pilot to help him. Together they put all their weight into it, and pulled back for all they were worth. As the men pulled with all their might, suddenly by shear brute force, the aircraft began to recover from the dive and they were on their way back to base. Later that month P/O J.R. Dudley was awarded the DFC for his courage and skill as a pilot. Lindsay always credited P/O Dudley for saving his life that day. On nights when he wasn’t flying he enjoyed sitting off by himself in the desert looking up into the night sky. This is when he felt closest to God, and would often take his Methodist hymn book with him to read.

He flew throughout July and August, with some time off to visit some of the holy spots of Palestine and some time at the beach. The break was important to the stressed aircrew. In September his crew crash landed in the desert. The crew slept during the heat of the day and walked at night until they were picked up by British forces. After verifying their identities they were returned to base at Abu Sueir.

On 1 October Lindsay was promoted to Warrant Officer. A tour of operations was considered to be 30 operational flights. Lindsay completed an official tour of operations in the month of September, but continued flying with the squadron. He was yet to receive any further orders. They continued to fly, attacking shipping and jetties at Tobruk. Lindsay’s final operation was on 12 October 1942. He ended his tour as he had begun it – bombing enemy shipping at Tobruk. He was finished. The Air Force said so. He had completed a tour of 32 operations, and had logged a total of 251 hours and 50 minutes of operational flying. He was ordered back to Britain. On 23 October, the opening day of the Battle of El Alamein he said good-bye to his crew and 37 Squadron, and travelled to 23 PTC. Yet unknown to him, on the same day he was promoted to Pilot Officer. He would have to wait until his return to Britain to be notified of his promotion.

Lindsay’s return trip to Britain took a total of 87 days. He arrived back in Canada the end of March 1943. Within three months of his arrival home he married his sweetheart, Jean Hull. They enjoyed 62 years of life together, until his death in 2005. Lindsay spent the remainder of the war as a flight instructor at No. 9 AOS at St. Jean, Quebec, and finished with the rank of Flight Lieutenant. By war’s end he had in his possession an Air Observer’s Badge and Operational Wings. Over the course of his service in the RCAF Lindsay had also earned four medals: Africa Star and Clasp; Defence Medal, General Service Medal, and Canadian Volunteer Service Medal. In Canada these medals were not automatically issued to deserving veterans. In the RCAF the onus was oddly on the veteran to make application for any medals he had earned. Lindsay would not apply for the medals that he had earned and was entitled to have, as he” saw no virtue in seeking reward for doing one’s duty”. He had simply done his duty, nothing more, and that was all.

In July 1945 he registered in the Engineering program at McGill University. Upon graduation he was employed by Shell Canada, and continued with them as a chemical engineer until his retirement in 1983. For a more detailed read on the life and service of Lindsay Reynolds see Duty With Honour: The Story of a Young Canadian With Bomber Command