|

|

|

10th April 1940On this day:

If you can provide any additional information, please add it here.

|

Remembering those who died this day.

- Armstrong John Luney. Able Sea. (d.10th Apr 1940)

- Bailey Albert Jack. Ldg.Sea. (d.10th Apr 1940)

- Dorward Fred Pattison . Able.Sea.

- Fisher Joseph George James. Ldg. Sea. (d.10th Apr 1940)

- Flynn John Thomas. Able Sea (d.10th Apr 1940)

- Holehouse Cyril. Able Sea. (d.10th Apri 1940)

- Holt Alfred. Able Seaman (d.10th April 1940)

- Maddocks Frank. Sick Berth Attendant (d.10th April 1940)

- Maidlow Henry Richard Munden. Lt. (d.10th April 1940)

- Mann Samuel Henry. Able Sea. (d.10th Apr 1940)

- Mulhall Brendon. (d.10th Apr 1940)

- Mulligan Joseph . Canteen manger (d.10th APR 1940)

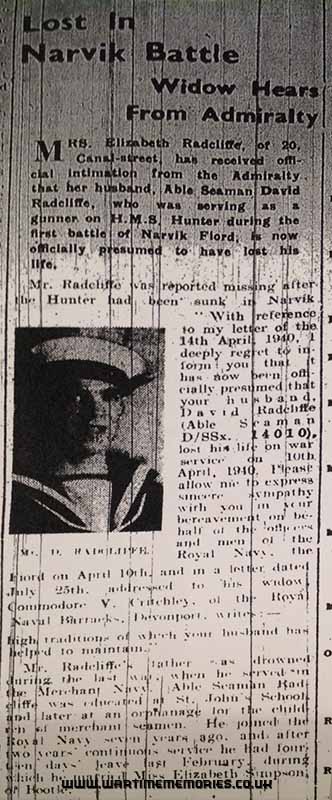

- Radcliffe David. Able Seaman (d.10th Apr 1940)

- Rowe James Stanley. Leading Steward (d.10th April 1940)

- Smart Harold Joseph. Stoker II Class. (d.10th Apr 1940)

- Stevens Bertie Hale. 1st Stoker. (d.10th April 1940)

- Warburton-Lee Bernard Armitage Warburton. Capt. (d.10th April 1940)

The names on this list have been submitted by relatives, friends, neighbours and others who wish to remember them, if you have any names to add or any recollections or photos of those listed,

please

Add a Name to this List

|

|

|

The Wartime Memories Project is the original WW1 and WW2 commemoration website.

Announcements

- The Wartime Memories Project has been running for 24 years. If you would like to support us, a donation, no matter how small, would be much appreciated, annually we need to raise enough funds to pay for our web hosting and admin or this site will vanish from the web.

- 22nd April 2024 - Please note we currently have a huge backlog of submitted material, our volunteers are working through this as quickly as possible and all names, stories and photos will be added to the site. If you have already submitted a story to the site and your UID reference number is higher than 263973 your information is still in the queue, please do not resubmit, we are working through them as quickly as possible.

- Looking for help with Family History Research?

Please read our Family History FAQ's

- The free to access section of The Wartime Memories Project website is run by volunteers and funded by donations from our visitors. If the information here has been helpful or you have enjoyed reaching the stories please conside making a donation, no matter how small, would be much appreciated, annually we need to raise enough funds to pay for our web hosting or this site will vanish from the web.

If you enjoy this site

please consider making a donation.

Want to find out more about your relative's service? Want to know what life was like during the War? Our

Library contains an ever growing number diary entries, personal letters and other documents, most transcribed into plain text. |

|

We are now on Facebook. Like this page to receive our updates.

If you have a general question please post it on our Facebook page.

Wanted: Digital copies of Group photographs, Scrapbooks, Autograph books, photo albums, newspaper clippings, letters, postcards and ephemera relating to WW2. We would like to obtain digital copies of any documents or photographs relating to WW2 you may have at home. If you have any unwanted

photographs, documents or items from the First or Second World War, please do not destroy them.

The Wartime Memories Project will give them a good home and ensure that they are used for educational purposes. Please get in touch for the postal address, do not sent them to our PO Box as packages are not accepted.

World War 1 One ww1 wwII second 1939 1945 battalion

Did you know? We also have a section on The Great War. and a

Timecapsule to preserve stories from other conflicts for future generations.

|

|

Want to know more about the 10th of April 1940? There are:24 items tagged 10th of April 1940 available in our Library There are:24 items tagged 10th of April 1940 available in our Library

These include information on officers, regimental histories, letters, diary entries, personal accounts and information about actions during the Second World War. |

|

Stories from 10th April 1940

|

AB. John Hague. Royal Navy, HMS Hunter. It may be of interest to some people to know that in the last couple of days the Royal Navy has located the fin

resting place of HMS Hunter, sunk in the first battle of Narvik.

I serve onboard HMS Albion at present, and we are conducting a wreath laying ceremony on saturday 8th March 2008

to honour the men who lost thier lives.

The memorial service,consisted on synchronised ceremonies on deck of each ship present and wreath laying over the site of the wreck.

After the ceremony, the ships, HMS Albion, HMS Bulwark, HMS Cornwall, RFA Mounts Bay and NOCGV Andenes, all turned in formation and steamed over the wreck, toasting the crew who perished with a tot of rum poured over the side.

As we sailed away, we signalled back by Morse: "Farewell, we'll meet again."

I'm sure more details will come to light in the near future. Yours aye LMEM "Ned" Kelly

Click here to see some photos of the ceremony

Able Seaman John Hague was a 19-year-old able seaman serving in the shell room below decks. as tehship went down he had no choice but to leap into the icy seas during a blizzard where he trod water until a German ship arrived and picked up survivors.

“I am so pleased and overwhelmed to know that after so many years HMS Hunter has been found and my fellow shipmates have a known resting place. I’m so sorry not to be able to go to the wreath- laying but I will be spending a quiet time at home with my family and thoughts, also my daughter in Cornwall will be laying flowers at sea for me dedicated to my shipmates.” Ned Kelly

|

AB. James Renshaw. Royal Navy, gunner HMS Hunter. My father Mr James Renshaw, has recently been featured in the local paper, as one of only a handful of survivors from the ill fated HMS Hunter, which was lost at Narvic in 1940. He is in contact with a few of the other survivors but would like to know if there are any others out there who might remember him. With the recent finding of the wreck of the Hunter, it has brought the memories flooding back after sixty eight years. I have in my posssesion a photograph with the caption HMS Hunter survivors camp Gunnarn Sweden 1940. This photo features thirty two of the ships company, and my Dad is second from the right, on the bottom row. (The only one not wearing a jacket)

Here is his story:

I was born in Sheffield. After an uneventful youth, I decided to join the Navy. My brother and I applied through the recruitment office; he failed and I was successful, so I finished up with a ticket to go up to Manchester to join the recruitment group, and I was sent down to Plymouth, in the Royal Navy. After my six months’ training, I was shipped out to the Mediterranean, to join a ship that had just been sunk. This is still actually in peacetime; it was the H.M.S. Hunter, and she was reputed to have hit a mine, but she sank down to a floating level. I joined her when she had been rebuilt. The first journey that we had was to join the Spanish Revolution that was taking place. We clued up in Barcelona and took out the British Consul and all of his employees, because Barcelona was being bombed.

We had one attack, which was by small Italian fighter planes. Meanwhile, the Germans were practicing their bombing technique on the poor Spaniards. After that, we did a cruise of the Mediterranean, then came home to Plymouth, and whilst we were back in Plymouth, restoring, threats from Adolph Hitler came along, and the ship finished up joining the South Atlantic Fleet to cut off two ships that were going to cut the trans-Atlantic cable. From that, we started doing convoy duty from Halifax Nova Scotia, in Canada, to Bermuda, picking up cargo ships, grouping them in Nova Scotia, for the journey across the North Atlantic. During this, we got into a hurricane, and we had to be convoyed ourselves, as we were so damaged.

After arriving in Plymouth again and being repaired, we went to cruise the North Atlantic again, and whilst we were doing the Iceland and Beyer Island run, we had a signal sent to us, to say that the Germans were invading Northern Norway, and would we kindly go up there and give them a thrashing? But it didn’t work out that way; being a junior member of the ship’s company, I was supplied with nothing more than an empty revolver. On querying as to what I was supposed to do with this thing, I was told that I’d be given ammunition when we arrived in Norway. Meanwhile, if I got into any trouble, I was to swing it around my neck. Anyway, the boat landing never came in. Whilst we were off Lofoten Island, where we’d gone to escort four mine-laying cruisers, we heard that the Germans were in Narvik and we were asked to kindly go in and sort them out. So on the tenth of April, at 4 a.m., we dashed into Narvik harbour, where there were twelve destroyers, each one with it’s own cover behind a merchant ship. Anyway, we sank four of them, then our captains decided we’d go in for a second helping, so we went in again, and by this time, the Germans were up and about, making certain alterations to their positions.

We charged in and Hardy, the sister ship of The Hunter, was driven aground. My ship, having learners aboard, was having a bit of difficulty with the smokescreen. There will be no record of this anywhere, not even the Admiralty will admit it, but we had quite a few greenhorns (rookies) with us, and they were given responsible jobs such as setting off the smokescreens. Now, there were three smokescreens on the destroyer, one is on deck, one is below deck and the other is the funnels themselves. This young lad, he lit a large canister, the size of a dustbin, but he didn’t have the strength to push it overboard, thereby ending the smokescreen. So now we’re trailing around Narvik Harbour with our smokescreen coming behind us. Smokescreens are produced to go into and out of, and our following destroyer went in and out of ours, but on coming out, it plunged into the Hunter, virtually cutting her in two. I was down in the shell room supplying the ammunition, when all of a sudden, a shout went out, “ABANDON SHIP!!” I was very cautious of abandoning ship in twelve degrees below freezing, because Narvik is an ice-free harbour; the tide is so strong that ice cannot form. Anyway, I got into a life raft, and that was the last I could remember until I found myself aboard a German ship. It was a whaler called the Jan Wellen.

We finished up as Prisoners Of War under the Germans in a schoolroom, high upon a hill overlooking Narvik Harbour. We had to join a couple of hundred Merchant Navy seamen, whose ships had been captured whilst anchored in Narvik, but that wasn’t the end of it. They decided that we were to be shipped out, because they couldn’t feed us; there was no food in northern Norway, so we were to be shipped over the border into Sweden, then into concentration. We joined a parade comprising seamen, sailors, Norwegian seamen, Norwegian fishermen on a death march from Narvik to Bejer Mountain, which is on the border between Norway and Sweden. It’s a posh ski hotel. Now, I, being who I am, decided that whilst we were in this hotel, we’d make the most of what we could, so I ventures into the bowels of the hotel, the basement. Of all things, I found a box with about a gross of unusually shaped chocolate bars. A chocolate bar in Norway and Sweden in those days was finger shaped, not a slab. Anyway, I finished up with these bars, plus two oranges. I took ‘em up to what we were using as sleeping quarters and I was forced to give them out to the ship’s company. This led to me being the urchin of the gang. I finally had to entrain with the land storm from Sweden, which is the equivalent of the W.V.S., who gave us tea, cigarettes and other things.

We were locked in railway coaches for a journey across Sweden. Various tactics were used to find out in which direction we were going, e.g.: if the sun is over here, the shadows will be over there, so early morning, we were heading eastwards. We arrived at a little church in a village called Gunarn. I became friendly with a little girl from outside of the barbed wire; she taught me Swedish. She wished to learn English and I wanted to learn Swedish, so between the two of us, we managed to make something of it. I learnt quite a lot, but the company we had, was taken away to another camp, because even being Navy trained, as I am, we were just that little bit above the standard required. We were then kept in one block; the Merchant Navy men all disappeared, we don’t know where they went. The next move was, the church authority decided we had been there long enough. It was a brand new church, it wasn’t blessed or anything. We had to go to another camp down in Helsingmo, which is another prison camp. Now there, I met up with a young lady, a head mistress of the local school who wished to learn English.

Now, some of the features of this co-operation were quite unique. I was taken in, and the family that took me in, clothed me and fed me to a standard that was way above that which my shipmates were receiving. I was accepted into the family. The reason being, was that whilst we in England, buy the Christmas turkey, they purchase a suckling pig. A huge van comes round, selling these suckling pigs, and the pigs are fed on table scraps until Christmas. Come Christmas, it gets the chop. They were all leaning over the sty where the pig is kept and the owner of the pig is crying his eyes out. “The pig is dying, the pig is dying,” was all I could get out of him. The pig was over here, then over there and it was shivering and they couldn’t figure out why. I found the answer; I shoved my hand into the straw and found that it was wet. So, we took out the wet straw and replaced it with dry straw, in goes the pig and there goes another medal for me. I was the hero of the village at the time.

Now, I was beginning to learn how to ski and all those other things that rich people do. I was becoming a local figure, insomuch as when we had our next move to a nearer camp, I was taken away for a holiday back to the first camp. Meanwhile, the British Consulate decided that we couldn’t run around like this, we’d have to be more suitably dressed. Being Englishmen, we were brought under the spotlight by the newspapers, and we were to be more suitably dresses. He never mentioned the fact that the supplies in our camp were the remnants of the 1914 — 18 situation. And you can imagine a chief stoker riding on the back of a horse, with an umbrella up and a bowler hat on; I personally had a velvet suit. But they decided that we should be measured and supplied with the necessary kit, so we all in turn received two grey shirts, a pair of grey trousers, shoes we had to provide ourselves; but we got this kit and we were beginning to look a little bit smart. That wasn’t the end of it; we knew there was something behind it.

Now, 2 ½ years are going by now, and I couldn’t get home, there was no outlet, yet it was a situation where Sweden was neutral. So the British Consulate came up with a system: they’d have three high speed boats, and they would dash in through the Skagerrak, into Gothenburg, load up during the night, with butter and coffee, dash out again, loaded with ball bearings and various other hardware pieces. They were running back with these small motor launches across the Kattegat, then the Skagerrak, into the North Sea and back to Newcastle. So he told them of this idea that in the harbour of Norway, in the Baltic Sea, there are numerous forts in which there were English owned cargo ships with no crews because they’d been imprisoned, so, would we man them? Well, obviously, yes, we’ll man ‘em. We navy men were given a job of fitting all these appliances that the navy could supply. I had a twin Lewis gun, 14 — 18 war vintage, two large sugar boxes full of ammunition, two rocket launchers on the roof, which, at the pull of a string, would launch rockets, which would open out a parachute with dangling wires, and they were supposed to make the planes run into them, but they were a total failure.

Anyway, I left that particular ship, did all the necessary alterations, and being the leader of the band, I was given the job of testing by a firm called, Trellyborne Gummy Fabriek which is Swedish for Trellyborne Rubber Factory. They’d invented a survival suit. Now this survival suit consists of a boiler suit in rubber, with gloves welded on, feet welded on, and a double zip up the front, one in brass followed by another one that closed two rubber grommets together. I had to test these, so we blasted a hole in the ice, whilst we were alongside, and I had the job of getting into the 20 feet thickness of ice, getting in and testing the suits. They were remarkably good, but extremely bulky, and they had a hood. When it came to personal use, you had to take your arm out of the sleeve; if you could get your arm out of the sleeve you could get it into your trousers pockets, and you’d have a kidney shaped flask. It wasn’t to drink out of, it was for other purposes. It was designed to facilitate urination.

Anyway, I finished up having to take six Lascars (Indians) as passengers. Now of six Lascars in that day, five would be workmen, one would be the boss man who would be in charge of the other five. He’d be collecting their wages and sharing out, and providing for their religious beliefs and all that. I had to train them how to put the suits on in an emergency. Anyway, came the day that we had to sail, so, there were twelve ships. I have a list and a certificate signed by Sir George Binney. He ran a system from whence we get the Binney Medal. He organised all these ships to come together, of from Gothenburg, and sailed together behind the icepack. But the big ships go in first, breaking the ice. Three of the ships did manage to make it to Newcastle. The one I was in, which carried Sir George Binney, was H.M.S. Dicto, the M.V. Dicto. Several of the ships, I still have the names of them, we had a wine carrier a Charente, which is a district in France, B.P. Newton, which was an oil tanker. The one I was on, H.M.S. Dicto, was a one-passage ship, she made one passage to South America, and they’d loaded the fuel carrying cargo holds with wheat, so there was wheat everywhere. There was no room at all for oil. She was imprisoned in a port much further up the harbour, in the Baltic. Anyway, we all gathered together and at four o’clock, we had the orders to sail. The unfortunate part about it was that the pilot who was to take us out to sea, had bought a local newspaper, and that paper reported the fact that the English ships were sailing. So all the Germans had to do was to come out and wait for us behind the ice. The first few ships were sunk, two or three of them got through, three of ‘em were captured and they finished up in Germany. The one I was on, because I had the chief with me, turned around in the ice, being a big ship, and finished up back in Gothenburg. The following day, there was a ruckus in the paper, “Why let these ships go?” I was called up with a friend of mine, to go to the Consul’s office

Now, we were living in the Salvation Army in Stockholm, and we had to turn up every day to see the Consul. I ran out, having only two shirts and one only has two collars, so I ended up wearing a silk scarf. The Consul called us in one at a time, and queried, “Why are you wearing a scarf, where’s your collar and tie?” I explained to him that I had one collar in the wash, and the other was dirty. “Well,” he said, “this won’t do y’know, you represent England, you know. Get that muffler off, and be available at six o’clock tonight.”

I’d had 2 ½ years in Sweden now, no sign or sight of anybody doing anything for me. We waited until six o’clock, then suddenly there’s a knock on the door. So we opened the door and there was a fellow in a chauffeur’s uniform. So we gathered what few belongings we had; I was in a trilby hat, burgundy raincoat, silk scarf and collars in my pocket, and any toiletries that I had. He said, “Jump in the car.” So we jumped into the car. It was absolutely black, we didn’t know where we were, we didn’t know where we were going, all we knew was that we were in the taxi. So we finally pulled up outside a door, so we rushed in and when we got in, there were two Norwegian gentlemen, young seamen, and we all got chatting. We didn’t know what we were there for. The fellow came back again and said, “Right, go in there and sit yourself down.” Now, in there, was a Pilots’ dressing Room. There was everything from helmets, to flying boots to jackets. So, what do we do with all that? Well, we got rigged up in all this lot and his last words were, “Watch out there, and when you see a flashing light, run, and run like you’ve never run before.” So we’re all sitting around waiting, and all of a sudden, a light flashed, and we all rushed across the tarmac, and we came to a Wellington Bomber with its side door open. We were virtually pulled in by an airman, and he said, “Sit there, sit there, sit there. That’s your seat and that’s your toilet, there’s a pack of sandwiches and there’s your coffee. When I go like this, pull your masks down and put them on.” So, we’re all sitting there, locked in, not knowing what to do. I wasn’t going to move off my seat for that toilet anyway. So, we could hear a rumbling and we knew we were under way; we knew we were going north. We flew up and finally climbed above the height of the German fighter planes from northern Norway, up towards the North Pole and came down into Scotland, where we landed. In the meantime, I was ‘took short’ because cold weather is a natural laxative. Anyway, we arrived at an airport in Scotland, and I jumped out and opened my bowels right there on Scottish soil.

We were then shepherded again, into the Officers’ mess, but they couldn’t accommodate us lying down, but we could use the lounge. Come next morning, someone decided we should have breakfast. Now, we found it very peculiar that a fighter pilot should have to pay for his breakfast; all the pilots from the fighter squad had to go in and buy their food. Anyway, we had a jolly good breakfast, y’know, we had not seen eggs and anything like that. So, a young fellow came round and wanted money. We’d no money, we’d just been in Sweden, so he said, “Somebody will have to sign for it.” So I signed my name for four breakfasts and four railway tickets from Scotland.

By dawn, we’d both decided, Stanley and I, that we’d both go back and report to the navy. We were kept incarcerated for a couple of hours until the big navy boss came. He took me to one side and he said, “Who won the cricket match at Lords this year?” We had been in contact with nothing, absolutely nothing. “Who won the cup then? Who won the Derby race meeting? “ I said, “I know nothing about any of that.” “Alright,” he said, “who’s that other bloke outside?” I said, “That’s my mate, Stanley Cooke, a seaman wi’ me. He’s been wi’ me for the last 2 ½ years.” “OK,” he said, “now you go out through that door there.”

So I went out through that door there, then he called Stanley in and asked him the same questions, the final one being, “Who’s that bloke in that room there?” “That’s Jim Renshaw,” he said, “I’ve been with him for 2 ½ years.” So they finally decided that, yes, we are English, yes we are navy men. “Oh, by the way,” he said, “don’t forget to report back down to barracks.” Now, we’d got to go from Scotland, on a wartime train down to Plymouth. It took us 24 hours to get to Plymouth. I obviously went to my fiancée’s house, much to her surprise Well, we decided that we’d report in at 9 o’clock in the morning, so I went to see the bloke, I went in on my own. He said, “Who are you?” I said, “I’m Jim Renshaw.” “What’s yer number?” I gave him my number, my service number. “What ship?” and I told him. “Are you sure?” “Yes!” “Who’s that fella out there?” I said, “That’s Stanley Cook. He’s been wi’ me for the last 2 ½ years. “Alright,” he said, “Oh,” he said, “before you go, come back Monday,” he said, “and have yer bloody hair cut.” That was my greeting. And Stanley had to go through the whole lot too.

Anyway, I rejoined the navy, and they were gathering the remainders of 45 survivors. They got them out from Sweden one way, and they got them out in other different ways and they got the whole 45 seamen there, doing one particular job. The job was cleaning out female gas masks. Of course, females used gasmasks as handbags as well, and what we turned out of those handbags was nobody’s business. A lot of rude stuff there was. We were there for weeks, following the same routine, doing nothing, because we’d signed the treaty. We signed that, declaring that we would not fight any more Germans. They’d taken our fingerprints, and if we were caught again, we’d be shot. We finally finished up back in the navy and there was so little that they could do with us, that they had to discharge us. So I was one of the few discharged.

Unfortunately, one of my other shipmates was on one of the other craft that was captured and he finished his time in Germany as a prisoner of war. I never saw Germany as a prisoner of war, I saw it in Norway. It’s an experience you have to live through to understand it. I eventually got married and I then joined the dockyard navy, a tug section of the Royal Navy; I join all the tugs in the dockyard. I served there for forty odd years, losing half my hand in the process. I received the Queen’s Medal.

But, you know, looking back, it was amazing how we learnt to live in such cramped conditions. 45 people in a cattle truck, a real filthy environment. We did it sleeping, standing up using one corner of the truck as a toilet. Then we were marching through twenty feet of snow, from this blasted hotel, it was on a border station between Sweden and Norway and it caters for the highfaluting skiing fraternity that we had in those days. We had Norwegians with us, and we asked, “How much further?” With their limited English, they’d say, “Four miles.” Now four miles is 6 ½ kilometres, which is a considerably longer. It was actually somewhere in the region of 25 miles and it took us the best part of a week to cover it. It’s important to note that the men were naked, absolutely naked. They swam naked from the ship; they were picked up naked, taken to a school naked, then over the border naked. They had to be told to get onto a train. This was April the tenth in 1943; the sea temperature in Narvik was averaging 12 degrees below freezing. But due to the speed of the tide, it cannot form any ice.

I can recall the ship going down and I know she’s still down there. The Norwegians have made a museum of a couple of them. I’ve never managed to get back up there to, shall we say, have a look at it all? I lost every possession I had, including my bankbook, all my kit, everything went, and I finished up……….what did I finish up in? I was naked when I woke up. I was on a bunk with the chief stoker nursing me and I managed to scrounge a pair of canvas trousers, and a jersey of sorts, and in the next cabin to me was a civilian. They wouldn’t give him any leeway, but we got rumours that he was a relative of Winston Churchill. I became friendly with him, and all of a sudden, he disappeared and left his cabin open, and he left a pair of fisherman’s Wellingtons, so I nabbed them, but they were much too big. He was never heard of again. Of the Officers that were salvaged, we had one of them dead, and they made us carry him; I didn’t carry him, four lads carried him. He was dead and his entire bowel was hanging out, so I stopped the four of them and shoved it under his life jacket. Then they finally decided to cover his face and turn him over and take him away, and away he went. The Germans took him and they took the only living officer we had. I’ve never seen him since. From close on 200 seamen on the ship, only 45 of us survived. Most of ‘em, being like me, we put up with 2 ½ years of it.

I make a point to my own children, that it they go to foreign places, then they must learn a little of the language. My learning of a little of the language has stood me in jolly good stead, insomuch as they permitted me to leave the camp and go and live privately, 200 miles away with a little family. And they fed and clothed me, in fact, the son of the family (they had sons and daughters), deferred his father’s Will, he didn’t want his father’s property. Somewhere in the woods, they own a portion of land, which they have turned over to me. They made it in my name, so, somewhere in Sweden is a plot of land that I can legally claim, but I’d rather not go back, no, I’d rather not go back.

James Renshaw

|

AB. Stanley William James "" Cook. Royal Navy, HMS Hunter. My late father also served on HMS Hunter at the battle of Narvic and was marched into Sweden by the Germans in those icy conditions of mid April 1940

I know the Germans made him sign a declaration promising never to engage the enemy again and during his capture he made a couple of unsuccessful attempts to escape

He returned to Devonport Naval Dockyard late 1943 where he served out the remainder of the war in HMS Drake a shore base but never liked it He resided in Devonport After the war he joined the Merchant navy He passed away in 1990 in Plymouth Devon

If any surviving ship-members can recall my Dad -Stanley Cook (cookie)please let me know Jim Cook

|

Able Seaman Alfred Holt. Royal Navy, HMS Hunter. (d.10th April 1940) My Grandfather served and died aboared HMS Hunter, he was a torpedoer he is buried in Narvick where his body was washed ashore. I'm afraid this is all I know because my Father was only 9 months old when it happened.Gavin Holt

|

Canteen manger Joseph Mulligan. Navy Army and Air Force Institute, H.M.S Hunter. (d.10th APR 1940) My uncle was on board H.M.S Hunter, when it sunk on the 10th April 1940. His name was Joe Mulligan. He was a canteen assistant and just 21 years old. If anyone remembers him or knows anything about him I would love to know.Vince Mulligan

|

Stoker II Class. Harold Joseph Smart. Royal Navy, HMS Hunter. (d.10th Apr 1940) Harold Smart was killed at sinking of HMS Hunter.Simon

|

Brendon Mulhall. Royal Navy, HMS Hunter. (d.10th Apr 1940) Brendan Mulhall was my Uncle, my Mother's brother. She had a photograph of him in his Navy uniform on display in her home in Ardglass and I knew him only through that photo. I was born in 1947 so I never new him. He did not survive the sinking of the Hunter and I believe he is buried in Narvik. I would be gratefull for any information.Clement Milligan

|

Able Sea. Samuel Henry Mann. Royal Navy, HMS Hunter. (d.10th Apr 1940) Tom Mann

|

Leading Steward James Stanley Rowe. Royal Navy, HMS Hunter. (d.10th April 1940) NOTE: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Hunter_(H35)Susan Phillips

|

Sick Berth Attendant Frank Maddocks. Royal Naval Auxiliary, HMS Hunter Sick Berth Reserve. (d.10th April 1940) Frank Maddocks was my maternal grandfather. He died when HMS Hunter sank. His youngest daughter (my mother) was only 18 months old at the time. His wife, Annie, raised their two girls on her own with help from Legacy. She never remarried.Martin Kitchen

|

Capt. Bernard Armitage Warburton Warburton-Lee. VC. Royal Navy, HMS Hardy. (d.10th April 1940) Captain Bernard Armitage Warburton Warburton-Lee was 44 years old, and a captain in the Royal Navy when was awarded the VC.

"On 10th of April 1940 in Ofotfjord, Narvik, Norway, in the First Battle of Narvik, Captain Warburton-Lee of HMS Hardy commanded the British 2nd Destroyer Flotilla consisting of five destroyers, HMS Hardy, Havock, Hostile, Hotspur and Hunter, in a surprise attack on German destroyers and merchant ships in a blinding snowstorm. This was successful, and was almost immediately followed by an engagement with five more German destroyers, during which Captain Warburton-Lee was mortally wounded by a shell which hit Hardy's bridge. He was awarded the Victoria Cross, posthumously. His citation reads as follows:

"For gallantry, enterprise and daring in command of the force engaged in the First Battle of Narvik, on 10th April, 1940. On being ordered to carry out an attack on Narvik, Captain Warburton-Lee learned that the enemy was holding the place in much greater force than had been thought. He signalled to the Admiralty that six German destroyers and one submarine were there, that the channel might be mined, and that he intended to attack at dawn. The Admiralty replied that he alone could judge whether to attack, and that whatever decision he made would have full support. Captain Warburton led his flotilla of five destroyers up the fjord in heavy snow-storms, arriving off Narvik just after daybreak. He took the enemy completely by surprise and made three successful attacks on warships and merchantmen in the harbour. As the flotilla withdrew, five enemy destroyers of superior gunpower were encountered and engaged. The captain was mortally wounded by a shell which hit the bridge of H.M.S. Hardy. His last signal was "Continue to engage the enemy"."

His was the first VC to be gazetted in the Second World War. S. Flynn

|

Able Sea John Thomas Flynn. Royal Navy, HMS Hunter. (d.10th Apr 1940) My mum's cousin John Thomas Flynn died when the Hunter sank in 1940. He was 19 years old, just wondering if there are any photos of the crew or anyone that served on the Hunter with him who might remember him?Les Edwards

|

Able Seaman David Radcliffe. Royal Navy, HMS Hunter. (d.10th Apr 1940) David Radcliffe was my Great Uncle and joined the Royal Navy in 1933. He served in HMS Barham, HMS Queen Elizabeth, HMS Active and HMS Hunter. He was married only two weeks before he died. I do not know much about his Naval Service except for information obtained from his Certificate of Service. If any survivors from HMS Hunter knew my Great Uncle or served with him in any of his other ships then I would like to hear from them. Ronnie Walsh

|

1st Stoker. Bertie Hale Stevens. Royal Navy, HMS Hunter. (d.10th April 1940) Bertie Stevens was my grandfather. He was 1st Stoker on HMS Hunter and went down with the ship when it sank at Narvik in 1940. If there is anyone still surviving and knew my grandfather, I would like to make contact with them. I have a photo of him also a memorial postcard.

Christine Gibbens

|

Able.Sea. Fred Pattison Dorward. Royal Navy, HMS Hunter. My mother was married to Fred Pattison Dorward. They were married for only 7 weeks when he was killed on the HMS Hunter at the Battle of Narvik along with petty officer James Smail whose widow became a great friend of my mother.

|

Able Sea. Cyril Holehouse. Royal Navy, HMS Hunter. (d.10th Apri 1940) Cyril Holehouse died on 10th April 1940 and is commemorated on the Plymouth Naval Memorial. I am trying to find information as he was my mother-in-law's older brother, who was on HMS Hunter for the Battle of Narvik. We believe he would have been around 20 years old in 1940. We know nothing of what happened to him on the day of the battle and would love to hear from anyone who has information, no matter how small.

Yassie Duck

|

Ldg.Sea. Albert Jack Bailey. Royal Navy, H.M.S. Hunter. (d.10th Apr 1940) Albert Bailey was the son of Robert James Bailey and Elizabeth Margaret Bailey, nee Swinnock, born 16th of November 1908 at Weymouth.

His father, Robert James, also served in the Royal Navy and was a Chief Petty Officer serving on H.M.S. Tipperary at the Battle of Jutland, where Robert was killed.

Albert enlisted in the Royal Navy on 20th of May and was serving on the H Class destroyer HMS Hunter when the ship was lost during the first Battle of Narvik.

|

|