|

|

|

Those known to have served with Royal Canadian Artillery during the Second World War 1939-1945. - Anstruther-Gray MC William John St Clair. Mjr.

- Bailey Ernest.

- Bailey Ernest.

- Bannerman Gordon. Sgt Major

- Bolton Walter Gladwin.

- Breithaupt Arthur L.. Lt.

- Brooke Harold. WOII.

- Chapman Jack.

- Clayton Thomas F. P. .

- Doheny Daniel O'Connell. Lt.

- Doohan James. Lt.

- Dowden Walter Roy. L/Sgt. (d.9th Jun 1944)

- Harcourt Bruce. Gunner

- Johnson Vernon.

- Kearney Joseph Francis Kieran.

- Killingback Stanley Harold. 1st.Lt.

- Larson Gerald Peter. Gnr.

- LeMesurier MC James Ross. Lt.

- Mackay John. Pte.

- Mahoney VC John Keefer. Mjr

- McGuire George Taylor. Gnr.

- Morley Leonard. Rflmn. (d.15th Sep 1941)

- Morrow George Dixon. Capt. (d.30th Mar 1941)

- Osborn VC John Robert. Sgt.Major (d.December 19 1941)

- Parker Richard. Pte. (d.13th Dec 1942)

- Payne Orme.

- Richards John Leonard. Pte.

- Robinson John T..

- Savage James R.. Sgt. (d.10th July 1943)

- Smith MID. Wilmot Aubrey. Gnr.

- Sopp Roy Harry Watson.

- Spencer Jack. Capt.

- Spencer Jack. 2nd Lt.

- Walker Stanley James. F/Lt.

The names on this list have been submitted by relatives, friends, neighbours and others who wish to remember them, if you have any names to add or any recollections or photos of those listed,

please

Add a Name to this List

Records of Royal Canadian Artillery from other sources.

|

|

|

The Wartime Memories Project is the original WW1 and WW2 commemoration website.

Announcements

- The Wartime Memories Project has been running for 24 years. If you would like to support us, a donation, no matter how small, would be much appreciated, annually we need to raise enough funds to pay for our web hosting and admin or this site will vanish from the web.

- 18th April 2024 - Please note we currently have a huge backlog of submitted material, our volunteers are working through this as quickly as possible and all names, stories and photos will be added to the site. If you have already submitted a story to the site and your UID reference number is higher than 263925 your information is still in the queue, please do not resubmit, we are working through them as quickly as possible.

- Looking for help with Family History Research?

Please read our Family History FAQ's

- The free to access section of The Wartime Memories Project website is run by volunteers and funded by donations from our visitors. If the information here has been helpful or you have enjoyed reaching the stories please conside making a donation, no matter how small, would be much appreciated, annually we need to raise enough funds to pay for our web hosting or this site will vanish from the web.

If you enjoy this site

please consider making a donation.

Want to find out more about your relative's service? Want to know what life was like during the War? Our

Library contains an ever growing number diary entries, personal letters and other documents, most transcribed into plain text. |

|

We are now on Facebook. Like this page to receive our updates.

If you have a general question please post it on our Facebook page.

Wanted: Digital copies of Group photographs, Scrapbooks, Autograph books, photo albums, newspaper clippings, letters, postcards and ephemera relating to WW2. We would like to obtain digital copies of any documents or photographs relating to WW2 you may have at home. If you have any unwanted

photographs, documents or items from the First or Second World War, please do not destroy them.

The Wartime Memories Project will give them a good home and ensure that they are used for educational purposes. Please get in touch for the postal address, do not sent them to our PO Box as packages are not accepted.

World War 1 One ww1 wwII second 1939 1945 battalion

Did you know? We also have a section on The Great War. and a

Timecapsule to preserve stories from other conflicts for future generations.

|

|

Want to know more about Royal Canadian Artillery? There are:35 items tagged Royal Canadian Artillery available in our Library There are:35 items tagged Royal Canadian Artillery available in our Library

These include information on officers, regimental histories, letters, diary entries, personal accounts and information about actions during the Second World War. |

|

Thomas F. P. Clayton 23 Battery 1st Medium Regt Royal Canadian Artillery My brother, Thomas F.P. Clayton, 23 Battery, 1st. Medium Regiment was stationed at Borden, Hant's, England, in 1939/40 as a Canadian soldier. As he landed in England he recieved a letter "welcoming him to the shores of England, the son of Thomas James Clayton", (a British Beoer War Vetran and C.E.F. WW1 Vetran). He never got to even finish reading that letter as he was wounded, and it was lost in the English Hospital, and now he is requesting me to ask if it would be possible to get a copy of that letter or that type of historical document? Does anyone have a copy?

|

Vernon Johnson 3rd Battalion. Royal Canadian Artillery I am looking for information on two brothers from Albert who served in WWII. Vernon Johnson would have been with the RCA third battalion and Ross Johnson who was with the Princess Patricias Light Infantry. Any help would be appreciated.

|

Ernest Bailey 59th Newfoundland heavy Royal Artillery My father, Ernest Bailey, came from Trinity, Trinity Bay, Newfoundland. I'm trying to find anyone who knew my father or heard anyone mention his name when talking about their time in the war. My father went to northwest Europe with his regiment on the 4th July 1944.

My husband and I went to Trinity and donated his medals to Trinity War Museum. As his uniform was in the museum there I felt it was the place for his medals to be.

|

Ernest Bailey 59th Newfoundland heavy Royal Artillery My father, Ernest Bailey, came from Trinity, Trinity Bay, Newfoundland. I'm trying to find anyone who knew my father or heard anyone mention his name when talking about their time in the war. My father went to northwest Europe with his regiment on the 4th July 1944.

My husband and I went to Trinity and donated his medals to Trinity War Museum. As his uniform was in the museum there I felt it was the place for his medals to be.

|

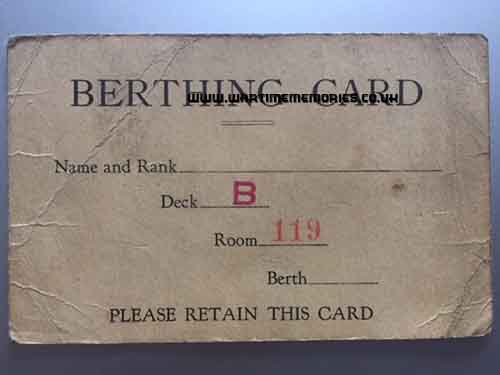

Capt. Jack Spencer Royal Army Ordnance Corps The sinking of the “Anslem”

Before the Second World War, one of my ambitions was to sail 1,000 miles up the Amazon on one of the Booth Line ships sailing regularly from Liverpool. The two vessels making this trip were the “Anselm” and the “Hildebrand” and the cost of the 100-day voyage was £100. Long before I was able to get anywhere near achieving my ambition the war came along and I quickly found myself a serving officer in the Royal Army Ordnance Corps.

After going through some training and service in the UK, I was notified in June 1941 that I was to go on seven days embarkation leave. Naturally, no indication was given as to my likely destination, but this was in fact the second time I had been destined for service overseas. On the first occasion in early 1940 my name was removed from the list of men due to leave for Singapore; this was because quite suddenly I had been selected for an immediate commission in the RAOC and I was required to report to an entirely new unit. This posting has nothing whatever to do with this story, but I mention it because many of my colleagues who did leave for Singapore finished their days on the Burma Railway project and in later years when on a business trip to Thailand I visited the British cemetery at Kanchnaburri – close by the bridge over the River Kwai. It was on that visit when the man in charge of the cemetery – which incidentally was beautifully maintained – allowed me to look through the long list of names of those who were buried there. I looked for the names of many of those with whom I had served and discovered that many of them had finished their days in the cemetery at Kanchnaburri. It was a very moving moment for sad reflection, the more so when I looked around and said to myself “There but for the Grace of God go I”.

At the risk of continuing this diversion from the main point of my story, it is worthy of recording that on this visit to Thailand I was working on a project for the World Bank and I was accompanied by a chap with whom I spent a lot of time while working for the Bank. The man to whom I refer was Japanese and during the war had actually worked on the survey and construction of the Burma Railway. When we went off on our duties on railway projects in various parts of the world it was the custom of this Japanese colleague of mine to wear a kind of field uniform with peak cap and high ankle boots similar to the uniform worn by Japanese soldiers during the war. On this particular visit to Kanchnaburri I knew in advance we would be visiting the cemetery so I told my colleague: “On this occasion please do not turn up in your usual outfit – wear something casual”. He was always willing to please and did as I asked, but the fact that he was with me made the visit even more emotional than it would have been without him.

I must now come back to my embarkation leave in June 1941. After the seven days were up I reported to a transit camp for officers at the Great Eastern Hotel on Marylebone Road in London. There I met several officers with whom I had trained in the early days after our commissioning; one of them was John Tucker who prior to the war was an executive with Marks & Spencer; another was named Barrie and he was a Shell employee. There were several more I knew well, but Barrie (I have forgotten his first name) was the comedian of the whole party and soon after we had our first briefings he made the comment: “We are bloody silly to come on this lark”. I may say these briefings of course gave us no indication at all of where we were destined for, but as we were issued with mosquito boots and other paraphernalia – including pith helmets – it was generally assumed that we were destined for West Africa – the White Man’s Grave! For this reason Barrie lost no opportunity at very frequent intervals to make his famous comment reminding us “We were bloody silly to go on this lark”.

After several days in London we boarded a train at some mysterious station I think near to Hammersmith. The train was a special one with only one stop – Liverpool. On arrival we marched down to the landing stage and, always having been keen on a sea voyage, I was delighted to see the magnificent Royal Mail ship “Reina del Pacifico” – she looked beautiful and our detachment made the for gangway. There we were advised that we had got to the wrong ship; the gangway man pointed a long way downwards to a very small vessel lying at the next berth. He said “That is your vessel – the Anselm.” Well, it looked a small ship but it was in fact about 6,000 tons and I was quite pleased to think I was at last going to sail on the Booth Line ship but I realised it was most unlikely we would be sailing 1,000 miles up the Amazon.

We eventually set sail with other ships from the Mersey and headed for the Clyde where we were marshalled with many other vessels to form quite a large convoy. On the trip to the Clyde the “Anselm” had shown signs of tending to limp along very slowly, but a few days after leaving the Clyde she was in quite serious trouble and was left behind by the convoy as she was quite unable to keep up the pace. The convoy did not have a very big naval escort and it must have been very difficult for the Commodore to reach his decision to allocate two of his corvettes to the “Anselm” and “Challenger” (a Royal Navy survey vessel). We made very slow progress and Barrie continued to remind us how silly we were to come on this trip. I was fortunate to get accommodation in a four-berth cabin with John Tucker, Barrie and John Dow, and considering it was wartime we had quite a pleasant voyage – for about a week!

For seven nights we were ordered to sleep with our clothes on as we were passing through an area at great risk from enemy submarines. On the eighth night we were considered to be safe and permission was given to sleep in pyjamas. However, on this particular night I was unable to get any sleep at all. I first went to my bunk at about 10.30pm; an hour later I got up, donned my dressing gown and walked all round the ship; on the boat deck it was a beautiful night with an oil calm sea. I looked all around and had a strange feeling of unease. I returned to my cabin and still I could not sleep. The other three occupants were fast asleep so I crept out again at 1.00am and again at 3.30am. On both occasions I marvelled at the beauty of the calm night, but I still had a most strange feeling of unease. It must have been 4.00am when I finally got to my bunk and at about 5.00am there was a low-sounding thud which seemed to knock the ship sideways from the port side.

Even though there was not a loud explosion I knew straight away that we had been torpedoed and my immediate thought was – that is why I have been uneasy and that must be what my subconscious mind had been anticipating. I jumped down from my bunk and believe it or not I had to waken the other three officers and tell them we had been torpedoed. At first they thought I was fooling, but when the lights went out and the voice from the bridge gave orders to abandon ship they were fully convinced. We all went up on deck with life jackets and minimum clothing. I surveyed the scene and saw the torpedo had struck forward and must have exploded in the troops’ sleeping quarters. Afterwards I learned it had blown away the escape ladders and the men could not get out. An RAF Padre, named George, asked to be lowered to the men, knowing he would never escape. It was a very brave and Christian act. Several years afterwards – it was after the end of the war – I read in the newspapers that the Padre had been awarded the George Medal posthumously.

The ship was sinking fairly quickly and the water was gradually creeping along the deck nearer and nearer to where I was standing with John Tucker at our lifeboat station. There was a lot of difficulty with the lifeboats; some were not lowered at all, while one was successfully lowered and filled with men when the next boat swung out and dropped on top of them. A lot of men threw rafts and other floatable material into the sea and then jumped in afterwards to their rescue platforms. This meant that some men already in the water got quite hefty stuff dropped on top of them. John Tucker and I watched all this and resolved not to jump until the water got close to our feet. While waiting for this to happen we could not help being amused to see an RAF officer clinging to a rope – he was in full service dress including peak cap – while trying to manoeuvre a raft with his feet so that he could get on to it, presumably hoping he would not get wet! There was also another humorous moment when our friend Barrie arrived on deck, exclaiming more convincingly than ever “I told you we were bloody silly to come on this lark!”

On looking around us I observed that the ”Challenger” and one of the corvettes were standing by to pick up survivors while the other corvette was sailing round dropping depth charges. I looked across to the “Challenger” and decided no matter what happened I could swim that distance – I should think it was no more than 500 yards. It was a strange feeling – for I had an inner feeling of confidence that I would make it. When the water crept up to us we did jump and I resolved to make a bee-line for the “Challenger”, but the strange thing is I remember absolutely nothing of the time I was in the water. This is not surprising for after I was eventually hauled up on the “Challenger” I developed the largest black eye I have ever had. This must have been caused by a small raft or other material dropping on me while in the water. I suppose I must have been in a pretty bad way for I was put to bed in an officer’s cabin on the “Challenger” and I must have slept for quite a long time.

The “Challenger” was a very small vessel and she picked up close on 600 survivors. The “Anselm”’s total complement – troops and crew – was about twelve hundred and I believe over three hundred men lost their lives. The morning after the sinking an armed merchant cruiser, the P & O liner “Cathay” arrived on the scene. She was not allowed to stop but lowered scrambling nets and we had to scramble up in quite a heavy sea. The Royal Navy men on “Cathay” were very kind and helped out with clothing and necessaries; eventually we put in to Freetown, Sierra Leone and later sailed in a small vessel “Surprise” to Lagos, Nigeria where I stayed for two years.

In Nigeria I landed a job in which I was very happy. I was in charge of an ammunition depot at Oshodi. I had five British NCO’s, about 100 African troops of the West African Frontier Force and a small army of casual labourers to handle the ammunition. I was the only officer on the depot and my house was a bamboo hut with palm thatch roof. The depot was about twelve miles from Lagos so I was pretty much my own boss.

Being so near to Lagos I was able to go into the city about once a week and I often used to attend the Saturday night dances at the Ikoyi club. On one of these visits there were several naval officers in the club – obviously from a vessel newly arrived in the harbour. One of these officers came over to me and said “Are you Captain Spencer?” I said that I was and to my amazement he said “You were on the Anselm, do you not remember me?” I had to admit that I did not remember him. He then informed me that he had been in charge of one of the lifeboats going around picking up survivors and he had a very full boat when they encountered me in the water. As he couldn’t get me in the boat he put a rope round my shoulders and dragged me along to the ladder of the “Challenger”. I suppose this account of what happened – and the black eye – together explain why I do not remember my time in the water!

Jack Spencer.

|

Jack Chapman Calgary Tanks Jack Chapman was amongst the Dieppe Canadians, who were with working party E608, which was a forest party near Hirschfelde. They also worked on E578 & E749.

|

Walter Gladwin Bolton I am trying hard to find my mother's father, Walter Bolton she never saw him nor knows much about him. Her mother was a nurse in WW2 in London and was in the Royal Canadian Artillery .all I've got to go on is what is on my mum's birth cert. He is down as Walter Gladwin Bolton bdr 28052 Royal Canadian Artillery {steel worker}.I can only find one Walter Bolton and he died in 1944 and is buried in Moro, Italy. On one paper it gives date of his death and said he has a one year old daughter he had never seen. The dates match my mother's birth. How can I be sure?

Editor's note: Walter Bolton buried at Moro has a different middle name, regiment and service number so is unlikley to be the same person. Check our Family History Hints & Tips for more sources to search.

|

Gunner Bruce Harcourt No.3 Btn. "B" Bty. Royal Canadian Artillery I've been told just recently that my father, Bruce Harcourt fell in love with a nurse here in Britain and her name was Olive Green. I understand they had a son but she left him before she told him she was pregnant in 1944.

I believe the area he was based in at the time was Northampton.

I would be grateful for any information anyone could give me as I would love to be able to find my older brother.

|

2nd Lt. Jack Spencer Royal Army Ordnance Corps The sinking of the Anslem

Before the Second World War one of my ambitions was to sail 1,000 miles up the Amazon on one of the Booth Line ships sailing regularly from Liverpool. The two vessels making this trip were the Anselm and the Hildebrand and the cost of the 100-day voyage was £100. Long before I was able to get anywhere near achieving my ambition, the war came along and I quickly found myself a serving officer in the Royal Army Ordnance Corps.

After going through some training and service in the UK, I was notified in June 1941 that I was to go on seven days embarkation leave. Naturally, no indication was given as to my likely destination, but this was in fact the second time I had been destined for service overseas. On the first occasion in early 1940 my name was removed from the list of men due to leave for Singapore; this was because quite suddenly I had been selected for an immediate commission in the RAOC and I was required to report to an entirely new unit. This posting has nothing whatever to do with this story but I mention it because many of my colleagues who did leave for Singapore finished their days on the Burma Railway project, and in later years when on a business trip to Thailand I visited the British cemetery at Kanchnaburri – close by the bridge over the River Kwai. It was on that visit when the man in charge of the cemetery – which incidentally was beautifully maintained – allowed me to look through the long list of names of those who were buried there. I looked for the names of many of those with whom I had served and discovered that many of them had finished their days in the cemetery at Kanchnaburri. It was a very moving moment for sad reflection, the more so when I looked around and said to myself "There but for the Grace of God go I".

At the risk of continuing this diversion from the main point of my story, it is worthy of recording that on this visit to Thailand I was working on a project for the World Bank and I was accompanied by a chap with whom I spent a lot of time while working for the Bank. The man to whom I refer was a Japanese and during the war had actually worked on the survey and construction of the Burma Railway. When we went off on our duties on railway projects in various parts of the world it was the custom of this Japanese colleague of mine to wear a kind of field uniform with peak cap and high ankle boots similar to the uniform worn by Japanese soldiers during the war. On this particular visit to Kanchnaburri I knew in advance we would be visiting the cemetery so I told my colleague: “On this occasion please do not turn up in your usual outfit – wear something casual”. He was always willing to please and did as I asked but the fact that he was with me made the visit even more emotional than it would have been without him.

I must now come back to my embarkation leave in June 1941. After the seven days were up I reported to a transit camp for officers at the Great Eastern Hotel on Marylebone Road in London. There I met several officers with whom I had trained in the early days after our commissioning; one of them was John Tucker who prior to the war was an executive with Marks & Spencer; another was named Barrie and he was a Shell employee. There were several more I knew well but Barrie (I have forgotten his first name) was the comedian of the whole party and soon after we had our first briefings he made the comment: “We are bloody silly to come on this lark”. I may say these briefings of course gave us no indication at all of where we were destined for, but as we were issued with mosquito boots and other paraphernalia – including pith helmets – it was generally assumed that we were destined for West Africa – the White Man’s Grave! For this reason Barrie lost no opportunity at very frequent intervals to make his famous comment reminding us "We were bloody silly to go on this lark".

After several days in London we boarded a train at some mysterious station I think near to Hammersmith. The train was a special one with only one stop – Liverpool. On arrival we marched down to the landing stage, and always having been keen on a sea voyage, I was delighted to see the magnificent Royal Mail ship "Reina del Pacifico" – she looked beautiful and our detachment made the for gangway. There we were advised that we had got to the wrong ship; the gangway man pointed a long way downwards to a very small vessel lying at the next berth. He said "That is your vessel – the Anselm!" Well, it looked a small ship but it was in fact about 6,000 tons and I was quite pleased to think I was at last going to sail on the Booth Line ship but I realised it was most unlikely we would be sailing 1,000 miles up the Amazon.

We eventually set sail with other ships from the Mersey and headed for the Clyde where we were marshalled with many other vessels to form quite a large convoy. On the trip to the Clyde the Anselm had shown signs of tending to limp along very slowly, but a few days after leaving the Clyde she was in quite serious trouble and was left behind by the convoy as she was quite unable to keep up the pace. The convoy did not have a very big naval escort and it must have been very difficult for the Commodore to reach his decision to allocate two of his corvettes to the Anselm and Challenger (a Royal Navy survey vessel). We made very slow progress and Barrie continued to remind us how silly we were to come on this trip. I was fortunate to get accommodation in a four-berth cabin with John Tucker, Barrie and John Dow, and considering it was wartime we had quite a pleasant voyage – for about a week!

For seven nights we were ordered to sleep with our clothes on as we were passing through an area at great risk from enemy submarines. On the eight night we were considered to be safe and permission was given to sleep in pyjamas. However, on this particular night I was unable to get any sleep at all. I first went to my bunk at about 10.30 pm; an hour later I got up, donned my dressing gown and walked all round the ship; on the boat deck it was a beautiful night with an oil calm sea. I looked all around and had a strange feeling of unease. I returned to my cabin and still I could not sleep. The other three occupants were fast asleep so I crept out again at 1:00 am and again at 3.30 am. On both occasions I marvelled at the beauty of the calm night but I still had a most strange feeling on unease. It must have been 4.00 am when I finally got to my bunk and at about 5:00 am there was a low-sounding thud which seemed to knock the ship sideways from the port side.

Even though there was not a loud explosion I knew straight away that we had been torpedoed and my immediate thought was – that is why I have been uneasy and that must be what my subconscious mind had been anticipating. I jumped down from my bunk and believe it or not I had to waken the other three officers and tell them we had been torpedoed. At first they thought I was fooling but when the lights went out and the voice from the bridge gave orders to abandon ship they were fully convinced. We all went up on deck with life jackets and minimum clothing. I surveyed the scene and saw the torpedo had struck forward and must have exploded in the troops’ sleeping quarters. Afterwards I learned it had blown away the escape ladders and the men could not get out. An RAF Padre, named George, asked to be lowered to the men, knowing he would never escape. It was a very brave and Christian act. Several years afterwards – it was after the end of the war – I read in the newspapers that the Padre had been awarded the George Medal posthumously.

The ship was sinking fairly quickly and the water was gradually creeping along the deck nearer and nearer to where I was standing with John Tucker at our lifeboat station. There was a lot of difficulty with the lifeboats; some were not lowered at all, while one was successfully lowered and filled with men when the next boat swung out and dropped on top of them. A lot of men threw rafts and other floatable material into the sea and then jumped in afterwards to their rescue platforms. This meant that some men already in the water got quite hefty stuff dropped on top of them. John Tucker and I watched all this and resolved not to jump until the water got close to our feet. While waiting for this to happen we could not help being amused at seeing an RAF officer clinging to a rope – he was in full service dress including peak cap – while trying to manoeuvre a raft with his feet so that he could get on to it, presumably hoping he would not get wet! There was also another humorous moment when our friend Barrie arrived on deck, exclaiming more convincingly than ever "I told you we were bloody silly to come on this lark!"

On looking around us I observed that the Challenger and one of the corvettes were standing by to pick up survivors while the other corvette was sailing round dropping depth charges. I looked across to the Challenger and decided no matter what happened I could swim that distance – I should think it was no more than 500 yards. It was a strange feeling – for I had an inner feeling of confidence that I would make it. When the water crept up to us we did jump and I resolved to make a bee-line for the Challenger but the strange thing is I remember absolutely nothing of the time I was in the water. This is not surprising for after I was eventually hauled up on the Challenger I developed the largest black eye I have ever had. This must have been caused by a small raft or other material dropping on me while in the water. I suppose I must have been in a pretty bad way for I was put to bed in an officer’s cabin on the Challenger and I must have slept for quite a long time.

The Challenger was a very small vessel and she picked up close on 600 survivors. The Anselm’s total complement – troops and crew – was about twelve hundred and I believe over three hundred men lost their lives. The morning after the sinking an armed merchant cruiser, the P & O liner Cathay arrived on the scene. She was not allowed to stop but lowered scrambling nets and we had to scramble up in quite a heavy sea. The Royal Navy men on Cathay were very kind and helped out with clothing and necessaries; eventually we put in to Freetown, Sierra Leone, and later sailed in a small vessel Surprise to Lagos, Nigeria, where I stayed for two years.

In Nigeria I landed a job in which I was very happy. I was in charge of an ammunition depot at Oshodi. I had five British NCO’s, about 100 African troops of the West African Frontier Force, and a small army of casual labourers to handle the ammunition. I was the only officer on the depot and my house was a bamboo hut with palm thatch roof. The depot was about twelve miles from Lagos so I was pretty much my own boss.

Being so near to Lagos I was able to go into the city about once a week and I often used to attend the Saturday night dances at the Ikoyi club. On one of these visits there were several naval officers in the club – obviously from a vessel newly arrived in the harbour. One of these officers came over to me and said "Are you Captain Spencer?" I said that I was and to my amazement he said "You were on the Anselm, do you not remember me?" I had to admit that I did not remember him. He then informed me that he had been in charge of one of the lifeboats going around picking up survivors and he had a very full boat when they encountered me in the water. As he couldn’t get me in the boat he put a rope round my shoulders and dragged me along to the ladder of the Challenger. I suppose this account of what happened – and the black eye – together explain why I do not remember my time in the water!

Jack Spencer

|

Pte. Richard Parker 7th Btn. Black Watch (Royal Highlanders) (d.13th Dec 1942) Richard Parker, son of Thomas W. and Mary Jane Parker (nee Jefferson) was born in Hebburn, County Durham, Great Britain in 1919. He was the husband of Jane Parker (nee Scott), also of Hebburn. Private Parker died aged 23 during the Western Desert campaign in the minefields of the village of Mersa Brega. He is buried at Benghazi War Cemetery in Libya, and is commemorated on the WW2 Roll of Honour Plaque in the entrance to Jarrow Town Hall, Tyne and Wear, Great Britain.

|

Pte. John "Daisy" Mackay C Btn. No.11 (Scottish) Commando Private John Mackay, son of Hugh Kenneth and Elizabeth Mackay and brother of Georgie Mackay, was a 16 year old farm servant when he enlisted with 5th Battalion Seaforth Highlanders in 1938. He left home on September 2nd 1939. In the summer of 1940, his time was spent patrolling remote sites in Wester Ross and Sutherland when he and some of his fellow soldiers decided to volunteer for the Special Service Brigade. He was then sent to Africa to join the 11th Commando.

John Mackay set off on his first patrol on 11th Oct 1941, destined for Kharga in the Libyan Desert. In Egypt, April 1943, the fit and healthy members of the Long Range Desert Group, of which John was now a member, were sent to train in Lebanon at the Mountain Warfare School. He was then ordered to fight for the Dodecanese Islands, and LRDG were sent to the island of Calino at the start of the campaign. On 20th October the Battle of Leros was underway, and British command gave the LRDG orders that the island of Levitha was to be captured immediately. On the night of 22nd October the commandos of ‘B’ Squad slipped into canvas assault boats and prepared to land on the nearby beach. Unfortunately they came under heavy machine gun fire and the end result was that there was no option but to surrender. John Mackay was officially captured by the Germans on October 24th 1943. The LRDG men taken prisoner on Levitha were first shipped over to Yugoslavia from where they began the long train journey to Germany. Private Mackay ended up a POW in Stalag 8b, Lamsdorf, Poland. In late January 1945 he made the journey to Trieste to work salt mines in northern Italy.

Once he was set free he had to make his way back to the British lines on foot, and once back in Britain he spent a period convalescing in hospital prior to coming home. John arrived at Fort George in March 1946, and was reunited with his family two months later.

|

John T. Robinson 166th (Newfoundland) Regiment, 59th Bty. Royal Artillery My father John Robinson was a full service soldier of the 166th Regiment, 59th Battalion. He served from 1939 to 1945 and was one of the many infantry who landed in Normandy. He stayed on the front lines for 13 months after June 6, 1944 and returned home at the end of the war. His battalion moved through France, the Netherlands and into Germany. He told very few stories of his experiences and died at the early age of 39 on June 20, 1959.

|

Pte. John Leonard Richards Royal Army Ordnance Corps My father John Leonard Richards was a dispatch rider captured in North Africa in May 1941. His family later were told he was in Stalag V11A. Where he stayed until the war ended. We know little of what happened to him there but he came home in poor health and was classed as disabled. Dad never spoke about anything to do with that part of his life. He died in 1973 aged 58 yrs old. Soon after his death a fellow prisoner came looking for him and told us Dad was tortured but gave us no details. It's good to think he will be remembered via this site thank you.

|

Lt. Daniel O'Connell Doheny Royal Canadian Artillery Lieutenant Daniel O'Connell Doheny was captured during a raid on Dieppe and spent the rest of the war as a POW at Oflag 7b.

|

1st.Lt. Stanley Harold Killingback HMS Saint Wistan Stanley Killingback was my father and I only know that he served from 9th October 1944 to 3rd May 1945 in West Africa.

|

Lt. James Doohan 13th Field Artillery Regiment Royal Canadian Artillery James Doohan was commissioned into the Royal Canadian Artillery and landed on Juno Beach on D-Day, leading his men through a mine field on Juno beach and personally taking out two German snipers in the process.

After his unit was secured in their position for the night, Doohan was crossing between command posts, when a Canadian machine gunner mistook him for the enemy and opened fire. Doohan was hit by four rounds in one of his legs, one in his hand, which ultimately resulted in him losing his middle finger, and one in the chest. The shot to the chest likely would have been fatal except that he had a silver cigarette case there, given to him by his brother, which deflected the bullet.

After recovering from his injuries, he became a pilot in the Canadian Air Force. Despite not ever flying in combat, he was once called “the craziest pilot in the Canadian Air Force†when he flew a plane through two telegraph poles after slaloming down a mountainside, just to prove it could be done. This act was not looked upon highly by his superiors, but earned him a reputation among the pilots of the Canadian Air Force.

Post war, James became an actor, preforming in over 4000 radio shows and 400 TV shows in Canada, being particularly noted for his great versatility in voice acting, but was most famous for his portrayal of Chief Engineer Scott in Star Trek.

|

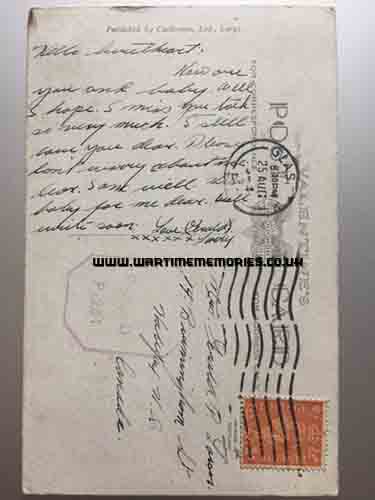

Roy Harry Watson Sopp 7th Medium Regiment Royal Canadian Artillery My mother, Rose Alice Marston, was a war bride. She was from Great Bookham and married on 24th of December1944 to my father Roy Harry Watson Sopp who returned to Canada in January, 1945. She was born on in 1923 and was 22 when she came to Canada. She would have boarded the train in Halifax around May 9-12 1945 and taken it to either Brandon or Winnipeg Manitoba.

My father returned home to Brandon Manitoba, after receiving shrapnel injuries near Caen in France in August 1944. He was a member of the Canadian II Corps, 7th Medium Regiment RCA, Gnr. Sopp, R.H.W.

From September 1939 until November 1943 when the 7th Army Field Regiment became the 7th Medium Regiment, many left the unit for a variety of reasons, but probably 800-900 of those listed were actually with the 7th Medium between November 1943 and the end of the war. I do know he was injured in France in mid August 1944. I live in Halifax, Nova Scotia, where I have the privilege of being able to visit Pier 21 and continue research of my mother's trip here in late April 1945. I have been searching for the name of the ship she travelled on and would love to hear from anyone who made the same voyage. At present I have learned she arrived in Halifax around May 5-8th 1945. Apparently, Pier 21 may have been in a state of repair following a fire there a few weeks prior. If anyone reads this and can provide any details, I would love to hear from you!

|

Sgt. James R. Savage (d.10th July 1943) James Savage is remembered on the Nassau Memorial in the Bahamas.

The Nassau Memorial commemorates Commonwealth servicemen of both World Wars who lie buried in cemeteries or churchyards, but whose graves have become impossible to maintain.

|

F/Lt. Stanley James Walker 490 Squadron My father, Stan Walker was posted to RNZAF 490 Squadron, Jui, West Africa on 14th od February 1945 where he flew Short Sunderland flying boats on anti U Boat patrols until 490 Sqd. was disbanded later that same year. He is still alive and fully independent at age 94.

|

WOII. Harold Brooke Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers My father, Harold Brooke, joined the R.A.O.C. on 5th August 1940 and then the R.E.M.E. on its formation on 1st October 1942 and served until he was demobilised on 23rd January 1946. He was an electrician by trade.

I know very little about his service except that he was stationed in or near Dover in 1944 as he met and, in December, married my stepmother that year. His first wife, my mother, had died of cancer in December 1943.

During his service in Dover he worked on radar installations and the cross-channel guns.

I know he was in (West?) Africa at some time, probably pre-1944, and was stationed in Holland for a period following the D-Day invasion. Regrettably I have no other information about his service.

|

Rflmn. Leonard Morley 1st Battalion King's Royal Rifle Corps (d.15th Sep 1941) My great-uncle Len Morley was killed serving with 1st KRRC in the Western Desert. He was 21 years old. He is buried at Sollum in Egypt, near the Libyan border. His younger brother John was wounded on 7th June 1944 in France but survived the war, despite regular returns to hospital, until he died in 1991.

|

Capt. George Dixon Morrow 2nd LAA Regiment Royal Canadian Artillery (d.30th Mar 1941) Captain George Morrow was the Son of William and Esther Ann Morrow.

He was 56 when he drowned.

He is buried in the Ballinakill (St. Thomas) Church of Ireland Churchyard, Ballinakill, Co. Galway, Ireland.

|

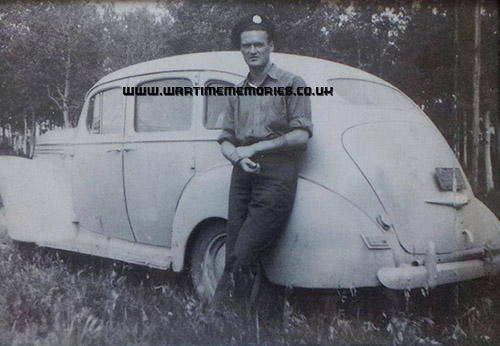

Gnr. Gerald Peter "Larry" Larson 23rd Field Regiment, 83rd Bty. Royal Canadian Artillery Gerald Larson served as a Gunner in the Royal Canadian Artillery for 2229 days between September 1939 and October 1945.

|

Lt. James Ross LeMesurier MC Scout Platoon Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders James Ross LeMesurier was born in Montreal on Nov. 26, 1923, the son of a law professor who went on to become Dean of Law at McGill. In spite of the family’s French name, they were very much English Canadian. The LeMesurier family traced its roots to the Channel Islands, off the British mainland.

Young Ross grew up in Westmount and went to Selwyn House, going on to boarding school at Trinity College School in Port Hope, Ont. A tall, muscular boy, he was a first-rate athlete and captain of the cricket, football and hockey teams as well as a keen squash player.

Straight out of high school he enlisted in the Royal Canadian Artillery. By March of 1943 he was promoted to lieutenant. He spent months training in Canada before being shipped to Europe in 1944 on loan to the British Army. The British Army was short of junior officers at the time, many of them having been killed in North Africa, Sicily, Italy and Normandy.

Lieut. LeMesurier was one of 673 “Canloans,” as they were called, young Canadian officers who volunteered for service in the British Army. The Canloans were all sent into battle, and thus suffered much higher casualty rates than the rest of the Army: Of 673 officers, 75% were killed or wounded, as opposed to regular losses of 50%.

Ross LeMesurier joined the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders, part of the famed British 51st Highland Division, which had defeated Rommel in North Africa. He was commander of the scout platoon. It was a dangerous appointment, as his men had to probe enemy defences before an attack or gauge whether the enemy was preparing a counterattack. Lieut. LeMesurier was wounded by rifle fire once, then by mortar fire in the Battle of Hochwald Forest in Germany in February, 1945. His leg was amputated below the knee at a field hospital. He was awarded the Military Cross for his bravery.

After the war he went on to become a highly successful businessman, finally retiring in 1983.

|

Lt. Arthur L. Breithaupt Calgary Tanks My father Art Breithaupt was taken prisoner at the raid at Dieppe on 19th of August 1942.

He had been in charge of several tanks in the Calgary Tanks Division. He referred to his tank as Betty.

He said very little to his family and friends about his imprisonment at Oflag VII B in Eichstatt, Bavaria. However, he did return to Canada in 1945 post war with a wonderful needlepoint that he had done at the camp. It is a scene of Oflag VII B.

|

Gnr. George Taylor McGuire 7th Medium Artillery Regiment George McGuire was my grandfather. He served in Europe with the 7th Medium Artillery Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery, 2nd Army Group RCA, 1st Canadian Army. He saw action in Normandy, the Seine, Boulogne, Calais, the Scheldt, Bergen op Zoom, and Nijmegen. In 1945 in Ems, the Rhineland, he was transferred to the 14th Armoured (Calgary Tank) Regiment.

|

Recomended Reading.Available at discounted prices.

|

|

|